Above water, they sound like bellowing Wookies. Below the ice, they sound like chirping, chattering robots. Either way, the Weddell seals of Antarctica should have no trouble finding work in an upcoming Star Wars project.

"The Weddell seals' calls create an almost unbelievable, otherworldly soundscape under the ice," Paul Cziko, a visiting professor at the University of Oregon and lead author of a new study describing the bizarre seal sounds, said in a statement. "It really sounds like you're in the middle of a space battle in Star Wars, laser beams and all."

The catch: You'd have to be an alien (or droid) to hear them; all of those sci-fi sounds are totally inaudible to human ears.

Cziko and his colleagues were able to detect the otherworldly noises after two years of listening to Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii) with a special hydrophone (an underwater microphone) installed in Antarctica's McMurdo Sound in 2017.

Before the researchers started recording, scientists knew about the 34 seal calls audible to human ears. Now, the team's research – published online Dec. 18 in The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America – adds nine new types of ultrasonic calls to the seals' repertoire. Those sounds include trills, whistles and alien-sounding chirps, sometimes composed of multiple harmonized tones.

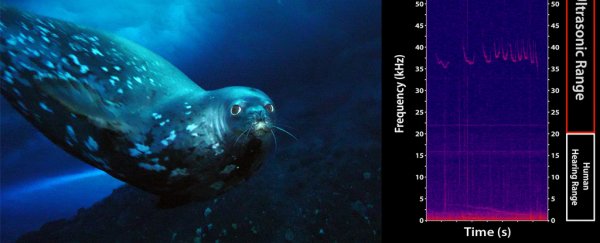

Humans hear in the sonic range of 20 to 20,000 hertz (or 20 kilohertz), the researchers noted. Most of the newfound seal sounds exceeded 21 kHz, with some consistently rising to 30 kHz.

(McMurdo Oceanographic Observatory)

(McMurdo Oceanographic Observatory)

Above: A visual representation (spectrogram) of one of the nine ultrasonic call types. The U-shaped features in the upper half of the plot are part of call type U101.

One high-pitched whistle reached a shrieking 49.8 kHz, the team wrote – and when seals harmonized multiple tones, the resulting noise could exceed 200 kHz. (That's well beyond the hearing range of cats, dogs and even some bats.)

What are all these high-frequency communications about? The researchers aren't sure; until now, scientists had never detected ultrasonic vocalizations in seals (nor in any other fin-footed mammals, like sea lions or walruses).

A diver in Antarctica's McMurdo Sound observes a Weddell seal. (McMurdo Oceanographic Observatory)

A diver in Antarctica's McMurdo Sound observes a Weddell seal. (McMurdo Oceanographic Observatory)

According to Cziko, the sounds could just be bonus conversational elements to "stand out over all the lower-frequency noise, like changing to a different channel for communicating."

It's theoretically possible that the noises are involved in echolocation, the biological sonar that animals such as dolphins and bats employ to find their way around dark places. But so far, there is no evidence that seals use echolocation, the researchers said.

Still, the behavior wouldn't be out of character for seals that can dive more than 1,900 feet (600 meters) below water and hunt in the darkness of Antarctic winter, the team added.

Let's see a Wookie try to do that.

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.