Centuries before first contact with Europeans, new research suggests a strain of tuberculosis was already circulating from the South American coasts to the mountains.

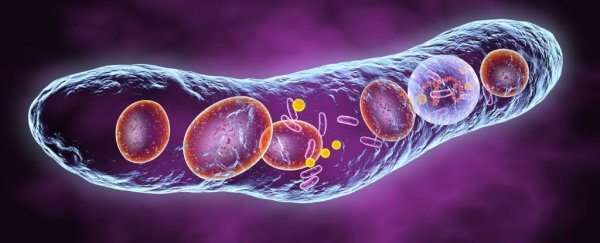

Deadly European diseases, like tuberculosis (TB), whooping cough, and smallpox, were spread around the world with colonization, but recent evidence indicates this wasn't the first time TB arrived in South America.

In 2014, researchers found the DNA of a bacterium related to Mycobacterium tuberculosis – the strain that causes tuberculosis in humans – in South American skeletons from about a thousand years ago, which is well before the arrival of Spanish, French and Portuguese colonizers.

Scientists have known for a while that TB can easily jump from one species of mammal to another; it's happened tens of thousands of times around the world. But the discovery of several ancient strains in South America suggests our history books might be slightly incorrect about the original spread of these bacteria.

The pre-contact bacterial strains found in 2014 carried the closest resemblance to M. pinnipedii, a strain found in marine mammals with flippers (pinnipeds), like seals and sea lions.

A genetic analysis then indicated that the most recent common ancestor for all genetically related Mycobacterium strains (known as the M. tuberculosis complex, or MTBC) emerged less than 6,000 years ago, pointing the finger at sea mammals as the potential first voyagers who carried TB across the ocean.

A new study has now found three more ancient strains of TB in the skeletons of people who lived in what is now inland Peru and Columbia. The skeletons were discovered far from the coastlines, and yet even here, over wide mountain ranges, TB appears to have been common, chronic and likely endemic in the local human population.

"These three new cases of pre-contact-era South American TB are from human remains that come from inland archaeological sites, two of which are situated in the highlands of the Colombian Andes," says anthropologist Tanvi Honap from the University of Oklahoma.

"All of these new three ancient TB genomes resemble M. pinnipedii – the same TB variant found in the ancient coastal Peruvian individuals and in modern-day seals and sea lions."

Archaeological evidence from inland Peru and Columbia suggests that local people here did not usually eat seal or sea lion meat traded from the coast. That means the pinniped-derived disease probably got this far inland via another host.

Instead of jumping directly from pinniped to these inland individuals, the bacterial strains would have likely crept inland over time, bouncing from human to human or spreading among other land mammals.

In New Zealand today, for instance, there are reports of TB jumping from seals over to grazing cattle, providing a bridge from sea creatures to land creatures.

"Colombia has a wide variety of terrestrial mammals, so M. pinnipedii could have been brought inland via the animal life," explains Honap.

"Or in a more likely scenario, it could have been brought inland via human-to-human transmission facilitated by trade routes, or a combination of both!"

Ultimately, European strains of TB replaced the original South American strains, disguising the deeper ecology of this bacterial infection.

Researchers are now teasing apart the complex history of the disease in precolonial times. Using genomic research, they hope to identify new strains of ancient TB to figure out how the illness became endemic in different locations at different times.

"[W]e believe that one or multiple separate introductions of M. pinnipedii from pinniped populations to human and/or terrestrial animal populations is currently the most parsimonious explanation for their spread to these inland locations," the authors conclude.

"Additional genomic data… from the pre-contact Americas will help develop these hypotheses further."

The study was published in Nature Communications.