Ten years ago, an archaeological curator by the name of Sara Rivers-Cofield bought a bronze Victorian-era silk dress at a shop in Maine.

Upon turning the skirt inside out, she discovered a hidden pocket containing a scrunched-up ball of papers.

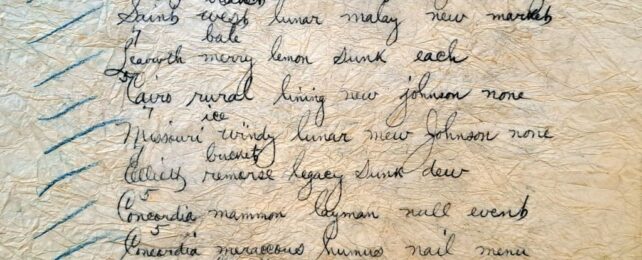

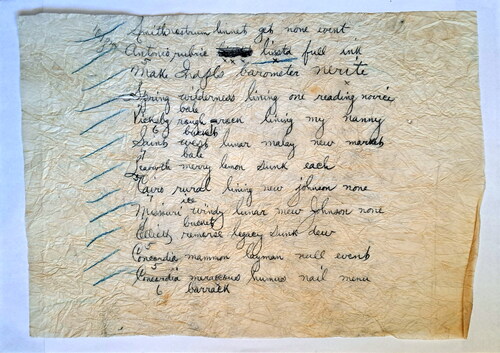

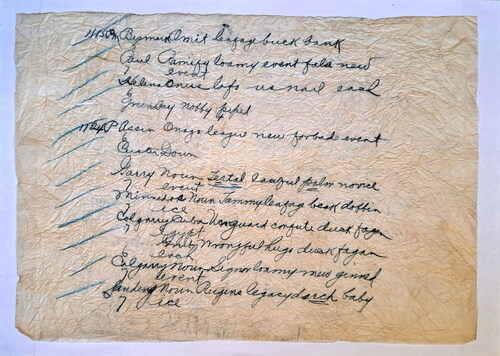

The sheets revealed two dozen lines of apparent gibberish once they'd been smoothed out, including phrases like "Grub wrongful hug duck fagan each" and "Calgarry Cuba Unguard confute duck fagan egypt".

For nearly a decade, these words, which Rivers-Cofield shared on her online blog, bamboozled code crackers the world over.

To some, the "Silk Dress cryptogram" was considered one of the top 50 unsolved codes and ciphers in the world.

At last, someone has cracked it.

Wayne Chan, a computer analyst at the University of Manitob in Canada has not only figured out what the words mean, he has pinpointed the day on which they were likely written: 27 May 1888.

"When the Silk Dress cryptogram was first published online, theories abounded about the content of the mysterious messages. Were they secret spy messages? Did they relate to illicit gambling?" writes Chan in a scientific journal for secret messages called Cryptologia.

"The reality of the messages being meteorological observations is somewhat more prosaic in nature."

As it turns out, the messages are a form of telegraphic code once used by the United States Army and Weather Bureau in the nineteenth century to share city forecasts as cheaply as possible. At this time in North America, each word on a telegram could cost several dollars, which, when you consider the currency's value before more than a century of inflation, translates to a big chunk of change.

While some telegraph codes are known to have been used commercially and on a wide scale, this particular code was only employed by a select group of government officials who were in charge of creating a national weather map.

Though hundreds of weather telegrams using this code were sent around the country every single day, Chan thinks the messages were all but worthless after translation and were, therefore, "rarely archived."

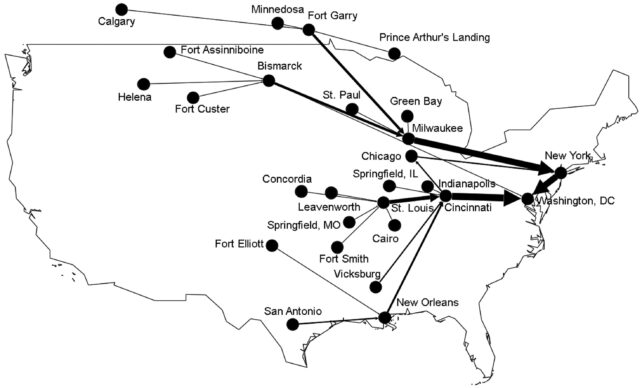

This is one of the only examples found to date, and it covers several American and Canadian stations mostly on the east coast but as far west as Calgary and as far south as San Antonio.

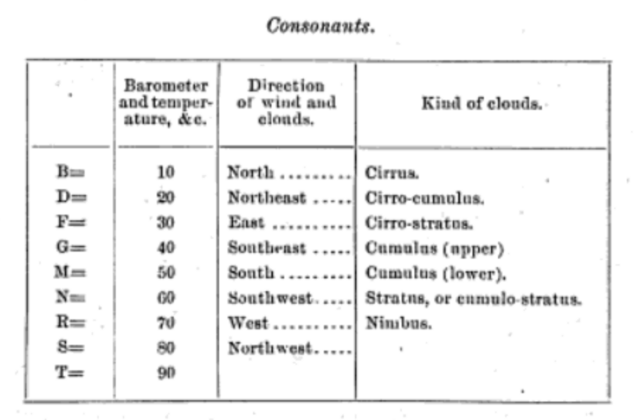

Thanks to a US Army codebook saved from 1877 and available online, the Silk Dress cryptogram now makes a whole lot more sense.

Here's how the code works.

According to the codebook, a typical 3 pm weather report could read "Memphis Target Kernel One Nile Bigot Tide".

The first word, 'Memphis', describes the station. The second word, 'Target' describes the pressure and temperature.

One word can describe both features because it can be broken down into two words.

Words beginning with vowels, for instance, can indicate values of pressure or temperature under 0.1. Words starting with consonants, on the other hand, can represent increasing pressures or temperatures based on their placement in the alphabet.

For example, if the second word in a weather code is 'Dundee', it is broken down into 'Du', which indicates a barometer of 0.2, and 'de', which indicates a temperature of 24 degrees.

The word 'Unfold', meanwhile, is broken down into 'U', which indicates a barometer of 0 and 'fo', which indicates a temperature of 38 degrees.

'Target' indicates a temperature of 44 degrees and a barometer of 0.92.

The next word in the sequence, 'Kernel', reveals the time of day and the dew point. 'One' and 'Nile' explain the wind and precipitation. 'Bigot' holds information about the wind velocity and maximum temperature, and lastly, 'Tide' is an indication of river height.

To make matters even more complicated, Chan realized that the weather codes from Canadian stations were formatted differently to the US ones on the silk dress papers.

Once he had decoded all the lines, Chan scoured national weather data from the US and Canada to figure out exactly what day was being described. It was most likely May 27, 1888.

Each local forecast on that day probably converged at a War Department telegraph room in Washington, DC. While no women worked here as operators, they did hold positions as clerks, copyists, typists, or book stitchers.

"It is therefore quite possible that the clerical staff may have handled the coded messages and that the owner of the dress could have been among them," suggests Chan.

Why this person tucked the numbers into a secret pocket, which Rivers-Cofield describes as "barely accessible", remains a mystery.

The name sewn into the silk dress is Bennet. For now, that's all we have to go on.

The study was published in Cryptologia.