The hidden scars left on the landscape during ice ages thousands to millions of years ago have now been imaged in spectacular detail.

Using a technique called reflection seismology, a team of scientists has imaged enormous gouges carved by subglacial rivers, buried hundreds of meters below the floor of the North Sea. Called 'tunnel valleys', these features can help us understand how frozen landscapes change in response to a warming climate.

"The origin of these channels was unresolved for over a century. This discovery will help us better understand the ongoing retreat of present-day glaciers in Antarctica and Greenland," said geophysicist James Kirkham of the British Antarctic Survey.

"In the way that we can leave footprints in the sand, glaciers leave an imprint on the land upon which they flow. Our new cutting edge data gives us important markers of deglaciation."

(James Kirkham)

(James Kirkham)

Above: A map reveals the location of channels buried beneath the North Sea with an overlay showing the ice sheet limits 21,000 years ago.

Reflection seismology, as the name suggests, relies on vibrations propagating underground to generate a density profile up to significant depths. It's a little like how we can use earthquakes to map the density of the interior of our entire planet, but targeted and on smaller scales.

In this case, air gun clusters were towed over a section of the North Sea. As these sound waves from these clusters propagated, hydrophones picked up the reflections as they bounced off structures of different densities below the seafloor.

Researchers then cleaned up and analyzed the high-resolution 3D data to build a layered map of the ancient landscape.

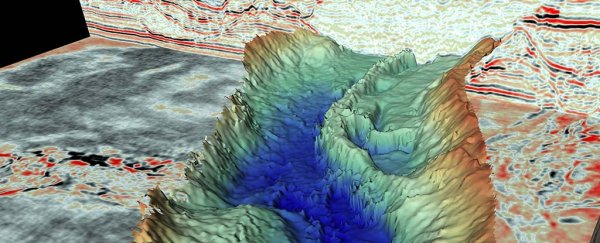

One of the tunnel valleys revealed by seismic data. (James Kirkham)

One of the tunnel valleys revealed by seismic data. (James Kirkham)

Even buried beneath up to 300 meters (984 feet) of sediment, this equipment is able to capture features as small as just 4 meters. This means that the data obtained is the most detailed to date on the tunnel valleys below the North Sea.

The data revealed 19 cross-cutting channels between 300 and 3,000 meters wide, with undulating thalwegs. Based on the morphology of these channels, the researchers interpreted them as tunnel valleys formed by meltwater running away underneath ancient ice sheets.

Because of the high level of detail, these channels reveal information about how the ice sheets interacted with the channels as they formed. Since the ice sheets found at Earth's poles today are currently undergoing melting in response to a warming climate, a better understanding of this process can help us figure out what is going to happen to Greenland and Antarctica in the future.

"Although we have known about the huge glacial channels in the North Sea for some time, this is the first time we have imaged fine-scale landforms within them," said geophysicist Kelly Hogan of the British Antarctic Survey.

A comparison of the tunnel valleys with current-day glacial features. (James Kirkham)

A comparison of the tunnel valleys with current-day glacial features. (James Kirkham)

"These delicate features tell us about how water moved through the channels (beneath the ice) and even how ice simply stagnated and melted away. It is very difficult to observe what goes on underneath our large ice sheets today, particularly how moving water and sediment is affecting ice flow and we know that these are important controls on ice behaviour," Hogan added.

"As a result, using these ancient channels to understand how ice will respond to changing conditions in a warming climate is extremely relevant and timely."

Future research, the team said, should involve shallow drilling, to place better chronological constraints on the tunnel valleys, as well as collection of a broader swath of seismic data.

This more granular detail will enable us to better model the hydrological systems of ancient ice sheets, and apply that knowledge to our current situation.

The research has been published in Geology.