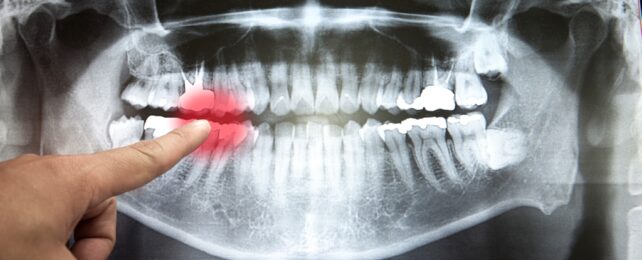

Losing a mouthful of teeth, as can happen in older age, has been linked to a greater risk of dying from heart disease, stroke, and other fatal heart events in a new analysis.

Studies before this have pointed to a link between missing one or more teeth and a higher risk of heart disease and cardiovascular diseases, more broadly.

Poor oral health is also a known risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), a group of conditions affecting the heart and blood vessels, which tallied together represent the leading cause of death globally.

It might sound like a strange connection, but it's plausible that tooth loss or poor oral hygiene could allow pesky pathogens to penetrate the gums, causing infections that seep into circulation and trigger inflammation that may affect the heart.

But there are a host of other factors playing into heart health and CVD risk, from smoking and exercise to diabetes, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure.

This has made it difficult for researchers to establish whether or not a causal connection between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease actually exists. Some studies suggest not – the association between tooth loss and CVDs disappeared once smoking was factored into a 2018 analysis – whereas others have yielded evidence supporting a causal link.

Attempting to clear up some of those contradictions, the new analysis focused on severe tooth loss, pooling data from 12 published studies that each tracked oral and CVD outcomes for between 3 and 49 years.

"Our findings clearly show that tooth loss is not just a dental issue, but a significant predictor of cardiovascular disease mortality," says Anita Aminoshariae, an endodontist and dental researcher at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

People who had lost all or most of their teeth had a 66 percent higher risk of dying from heart-related issues compared to those who had lost only a few pearly whites or none at all, the analysis found.

This association varied far more across the five studies that looked at people who had fewer than 10 teeth remaining than it did among the seven studies of people who had no teeth left to chew with.

But the elevated risk of dying from cardiovascular disease remained, evident among people who had lost roughly 22 or more chompers.

All 12 studies in the analysis adjusted for age and smoking status, and 10 of them considered at least five critical confounding factors associated with CVD risk.

When the researchers tested whether these factors affected their results, the heightened risk persisted, "confirming the impact of [severe] tooth loss on CVD mortality," Aminoshariae and colleagues write in their published paper.

While this analysis of observational studies can only point to associations, not direct causes, it suggests the global burden of CVDs could be partly addressed by improving oral health.

This could involve providing better access to healthy foods (instead of sugary, processed ones that cause dental cavities) and affordable dental care, especially in low- and middle-income countries and older populations.

In 2019, one-third of deaths worldwide were caused by CVDs including heart attack, stroke, clogged arteries, and heart failure.

"Thus, saving teeth and keeping an optimal oral health cannot be underestimated," Aminoshariae and colleagues conclude.

The study has been published in the Journal of Endodontics.