To properly navigate across the face of our planet, we need to use guidance from its magnetic field. And for that, we need to keep an accurate track of what that field is doing.

With that in mind, every five years scientists refresh a standardised model of the detailed wiggles and warps of Earth's magnetic field. But recently, things have gotten weird.

The current version of the World Magnetic Model (WMM) was released by the US National Geophysical Data Center on 15 December 2014. You'd think we don't need to worry about an update until December this year.

Not so. A news feature on Nature by Alexandra Witze highlights an urgent need for an expedited version of this all-important geophysical model of Earth's magnetic sphere.

Back in September, the NOAA released a quick-fix prerelease version of the WMM to keep everyone ticking until this new version - called WMM2015v2 - came out, but it's missing calculator, maps, and technical notes that come with the full updates.

An adjusted, comprehensive version of the WMM was expected to come out this week, but thanks to the shutdown of the US federal government, we'll now need to wait until the end of the month to see it.

It's none too soon - the current fix is already out of date.

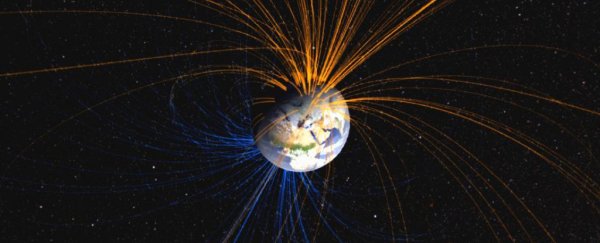

The WMM is a global map of deviations in the magnetic field lines that we expect to point the way to the poles. The one below is an example from 2010.

(NOAA National Geophysical Data Center)

(NOAA National Geophysical Data Center)

For your average weekend camper, a general sense that the magnetic field surrounding our planet runs perpendicular to the equator is all you really need to get the most from your trusty compass.

But not everybody can be happy with a ballpark estimate. Our high-school textbooks might show the magnetic field as a series of neat vertical lines, but the chaotic swirls of molten rock deep under our feet make this bubble of magnetism anything but tidy.

If you're in the transport business, or run operations for, say, a government's department of defence, those wiggles – or magnetic declinations – in the field could make a vital difference when you're trying to get from A to B.

That's where the WMM comes in. The model provides an estimate of how the ever-shifting magnetic field will look in the near future. Usually, the error margins of their predictions only become problematic after around five years.

During an annual check of the model in early 2018, researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the British Geological Survey smelled trouble.

Things were so far out of whack, that wiggle room was already at its limit, and they still had nearly two years until the update.

Geomagnetists have been keeping a close eye on the field in recent years, so have been aware that something is off.

Shortly after the release of the current model, researchers reported an intense region of magnetism accelerate over the northern part of South America, a movement the planners hadn't seen coming.

Meanwhile, a vast expanse of the magnetic field stretching from Chile to Zimbabwe has become so weak, it risks letting hazardous levels of radiation slip through and damaging the delicate electronics of passing satellites.

Then there is the meandering of the magnetic poles in what are referred to as excursions. The magnetic North Pole is making a break for Siberia, having recently crossed the international date line.

There is debate over whether such events foreshadow a complete reversal, or a long-period weakening of the entire field.

In short, nobody is really all that sure what's going on or how to predict these deviations. And some of those shifts have a bigger impact than others.

"The fact that the pole is going fast makes this region more prone to large errors," geomagnetist Arnaud Chulliat from the University of Colorado Boulder told Witze.

Researchers are feeding in several years of data to provide a short term fix to get us through 2019, with the usual update still planned for the end of the year.

Whether these kinds of fixes are going to become a regular event, or the five year lifespan of each version of the model needs a rethink, time will tell.

Geologists are working hard to figure out what kinds of underground weather events are causing these blips, and what it means for the future.

One thing is for certain – we're woefully unprepared if the field does anything too crazy.

Fingers crossed we'll be seeing that adjusted model online before February rolls around.