People in Europe were tweeting about a "dry cough" more than usual as early as January 2020, newly analysed data reveal.

While social media has played a key role in disseminating health information during the relentless COVID-19 pandemic, the new findings show it has the potential to be useful in other ways, too.

Authorities could be using such platforms to obtain real time, localised information about emerging viral hotspots before they're detected by official means, statistician Milena Lopreite from the University of Calabria and colleagues suggest in their new study.

"Our study adds on to the existing evidence that social media can be a useful tool of epidemiological surveillance," said economist Massimo Riccaboni from IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca.

"They can help intercept the first signs of a new disease, before it proliferates undetected, and also track its spread."

Within a dataset of over 570,000 unique users and more than 890,000 tweets, Lopreite and team searched for tweets from seven European countries with keyword " pneumonia" (in seven European languages) from last winter, and compared them with previous winters as far back as 2014.

After excluding links to news to take out mass media coverage, they found a significant increase in their keyword in most of the countries during the 20190-2020 winter, compared to previous years.

They repeated this with other terms for common COVID-19 symptoms like "dry cough" and once again found similar patterns.

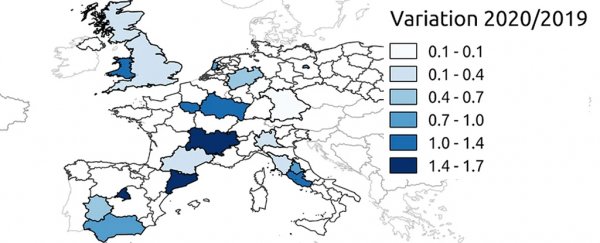

For Italy, the tweets showed signs of brewing virus hotspots in the first week of 2020 - weeks before the first case was officially announced on 20 February 2020. A similar pattern was seen in France. For Spain, Poland and the UK this social signal of COVID-19's presence appeared two weeks before their official cases.

These findings show just how much of a delay there can be between the presence of a new disease and our detection of it.

What's more, "whistleblowing came primarily from the geographical regions that turned out to be the key breeding grounds for infections," the researchers explained in their paper.

By integrating this information with data on environmental drivers like pollution, social media could prove a powerful tool for tracking new outbreaks, the team recommends.

Lopreite and colleagues note that this strategy is not a forecasting tool for unknown new diseases, because we do need to understand enough about the disease first - to know what to look for.

However, it could be a useful tool for tracking new waves of COVID-19 that are likely to arise once restrictions like social distancing are lifted around the world.

Between negative impacts on mental health to the spread of misguided or even fake news, relying on social media does have its risks. So it is clearly important that any new-found roles for these tools come with measures to keep them from being misused.

"Any integrated digital surveillance system set to monitor COVID-19 and beyond should be controlled by independent data protection and regulation authorities and adhere to a clear set of privacy-preserving and data-sharing principles that do not jeopardise civil rights and other fundamental liberties," the team cautions.

But given the likes of Twitter and Facebook are not going away anytime soon, we should certainly be trying to squeeze as much good out of these platforms as we can, while also sharing awareness of and working out how to rein in their shadier elements.

"These findings point to the urgency of setting up an integrated digital surveillance system in which social media can help geo-localise chains of contagion that would otherwise proliferate almost completely undetected," Lopreite and colleagues conclude.

So if (shudder to think) we do have to face another new pandemic, we now know: Once key symptoms have been identified, social media chatter could reliably reveal where outbreaks are occurring, ahead of other measures.

This study was published in Scientific Reports.