One of the most terrifying things about cancer is its perceived inevitability - when it comes to the many forms that are driven more by a person's genetics than their lifestyle, it often feels as though the most a patient can hope for is a fast diagnosis and successful treatment.

Which certainly isn't ideal, when you're talking about a disease that's debilitating at best, and fatal at worst. So researchers around the world are scrambling to come up with new types of medication that can act as cancer vaccines, triggering the body's immune system to stop tumour cells from taking hold on our various organs, tissues, and blood.

Known as immunotherapy drugs, researchers have found some success using these to treat prostate cancer, melanomas, and lung cancer, but until now, nothing seemed to work for breast cancer. Reporting in the journal Cell Reports this week, a team from the Houston Methodist Research institute has reported a new method of drug delivery that has been shown to significantly boost the body's immune response to breast cancer cells. In mouse models, at least.

"We could completely inhibit tumour growth after just one dose of the cancer vaccine in the animal model," said principal investigator, Haifa Shen, in a press release. "This is the most amazing result we have ever seen in a tumour treatment study."

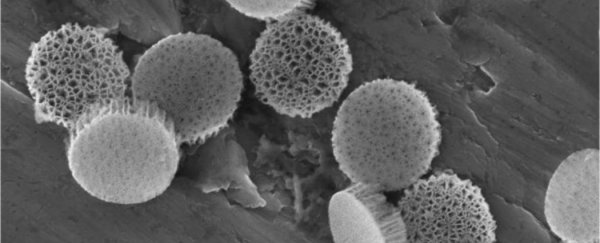

The team used porous silicon microparticles (PSM) - about 1 micrometre in diameter - to transport an immunotherapy drug to the site of breast cancer tumours, and in both in vivo and in vitro experiments, found that it stimulated a strong, and long-lasting immune response at local sites of tumour activity and growth - even without an antigen added to the mix. This means that the PSMs themselves are actually playing a role in fighting the cancer.

"The microparticles kicked off a potent immune response at tumour sites, altering the environment in a way that allows cytotoxic T cells to better perform the cancer cell-killing duties.

In what could have significant ramifications across the entire field of cancer research, the scientists found that the PSMs behaved this way whether or not they were loaded with antigens. This means that the microparticles have the potential to work with a variety of cancers."

"Besides developing a highly potent breast cancer vaccine, we have also demonstrated that PSMs are versatile," Shen said in the release. "This is a technology platform that can be applied by other scientists to develop vaccines for other types of cancers, ultimately helping, we hope, more types of cancer patients."