Having a fresh cut or sunburn on your skin when you first try a new food could increase the chances of developing an allergy to that food, suggests a new study led by the Yale School of Medicine (YSM).

Previous research has found that food allergies are more common in people with skin disorders like dermatitis, inspiring the team to investigate this mysterious connection further.

In experiments in mice, the team found that when new foods were introduced to the guts of the animals soon after damage to the skin, the mice developed allergic reactions to them.

The injuries boosted production of allergy-related antibodies, a reaction known as a humoral response. It's the first time that this overreaction from biological defenses, which can cause allergies, has been shown to work across such distant parts of the body.

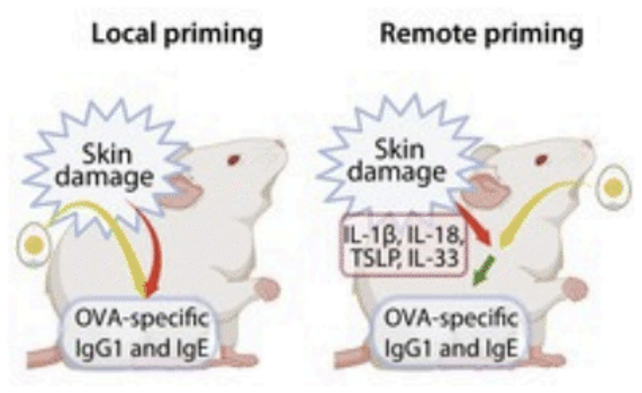

"In this study, we find that the systemic effects of skin inflammation are sufficient to initiate humoral responses to spatially uncoupled antigens, a concept that we define as 'remote priming'," write the researchers in their published paper.

We already know about the way allergens (substances triggering allergic responses) can take advantage of skin injuries to break into the body – something the researchers are terming 'local priming' in light of their new discoveries.

The experiments carried out here showed messenger molecules called cytokines triggering antibody reactions. It seems these molecules might be a crucial first step in remote priming, sounding an alarm in the gut when the skin is breached by injury.

This could cause the body to "blame" the distant injury on the new food, launching immune responses next time it's encountered.

All of this still needs to be confirmed in humans as well as mice of course, but the researchers are keen to identify the other cells involved in turning our stomachs against certain foods – with potentially disastrous results.

Our guts have evolved to be pretty tolerant when it comes to food and drink – it's easy to see why being fussy eaters can hold back a species in evolutionary terms – so if we're to understand food allergies, we need to know how this tolerance gets overridden.

"It's a mindset change that these things don't have to happen in the same place in the body," says dermatologist Daniel Waizman, from the University of California, San Francisco.

"We need to take a closer look at how these different organ systems talk to each other."

Researchers are making steady progress in understanding more about food allergies and how they affect our bodies – including what is and isn't an allergy – and this latest study adds some important new insight.

As well as improving our understanding of food allergies, and potentially offering a new pathway for treating them in the future, the study also tells us more about the impact of skin injuries beyond the visible cuts, grazes, and burns.

"To me these findings really highlight the importance of treating inflammation on the skin," says dermatologist Anna Eisenstein, from YSM.

"Treating skin disease is more than just treating what you see, but also the inflammation within and the potential for other systemic diseases."

The research has been published in Science Immunology.