In the ongoing efforts to control and treat Alzheimer's, one of the more promising avenues of research is using electromagnetic waves to reverse memory loss – and a small study using this approach has reported some encouraging results.

The study only involved eight patients over a period of two months, so we can't get too excited just yet, but the researchers did see "enhanced cognitive performance" in seven of the participants.

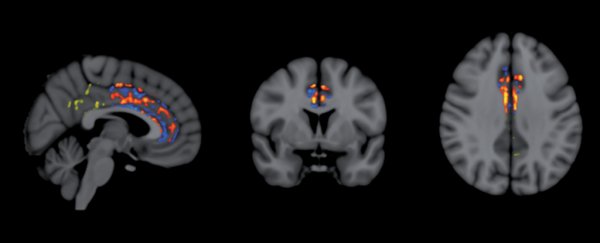

In this case, the volunteers – who all have mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease (AD) – were fitted with what's called a MemorEM head cap, which uses specially developed emitters to create a custom flow of electromagnetic waves through the skull. Treatments are applied twice daily, for an hour, and they can be easily administered at home.

(Arendash et al., 2019, Journal of Alzheimer's Disease)

(Arendash et al., 2019, Journal of Alzheimer's Disease)

The MemorEM device is being developed by NeuroEM Therapeutics, and we should point out that two of the authors behind the new study founded the company – so there is some vested commercial interest here.

That said, the research has produced a peer-reviewed, published paper, and shows some results that are definitely worthy of future investigation.

"Perhaps the best indication that the two months of treatment was having a clinically-important effect on the AD patients in this study is that none of the patients wanted to return their head device to the University of South Florida/Byrd Alzheimer's Institute after the study was completed," says biologist Gary Arendash, who is CEO of NeuroEM Therapeutics.

According to Arendash, one patient even said: "I've come back."

The study builds on previous research from the same team that concentrated on mice, which showed that this transcranial electromagnetic treatment (TEMT) was capable of protecting against memory loss, and even reversing it in older rodents.

Based on the evidence so far, TEMT looks like it can break up the toxic amyloid-beta and tau proteins that have been extensively linked with Alzheimer's – the waves are apparently able to destabilise the weak hydrogen bonds that hold them together.

These proteins essentially clog up the brain, scientists think, suffocating and destroying neurons we rely on to hold on to memories, turn thoughts into speech, and work out where we are in the world.

Using a commonly accepted set of tests designed to measure dementia, the impact of the electromagnetic waves was found to be "large and clinically important". This ADAS-Cog scale runs from an average of five for someone without Alzheimer's, to an average of 31 for those with Alzheimer's, and the study noted an average shift of more than four points in seven out of the eight volunteers.

That four point shift matches the sort of cognitive decline you might expect to see in Alzheimer's patients over a year – so it was as if a year of the impact of Alzheimer's on cognitive thinking had been rolled back in the space of just two months.

The advantage of this kind of treatment is that it can target the poisonous proteins directly and effectively. That's something that current drugs struggle with, thanks in part to the blood-brain barrier designed to keep our brains protected from foreign bodies.

What's more, the study showed the eight subjects showed no side effects or any signs of damage to the brain caused by the TEMT treatment.

Similar approaches are being tried by other companies – including Neuronix, which applies transcranial magnetic stimulation techniques via a head cap. We've still got a long way to go, but the signs are promising so far.

The next stage is a bigger trial involving more volunteers with AD – and NeuroEM Therapeutics has plans for a clinical trial involving 150 participants later this year. If that trial shows the treatment to be safe and effective, regulatory approval could follow.

"Despite significant efforts for nearly 20 years, stopping or reversing memory impairment in people with Alzheimer's disease has eluded researchers," says neuroscientist Amanda Smith, from the University of South Florida.

"These results provide preliminary evidence that TEMT administration we assessed in this small AD study may have the capacity to enhance cognitive performance in patients with mild to moderate disease."

The research has been published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.