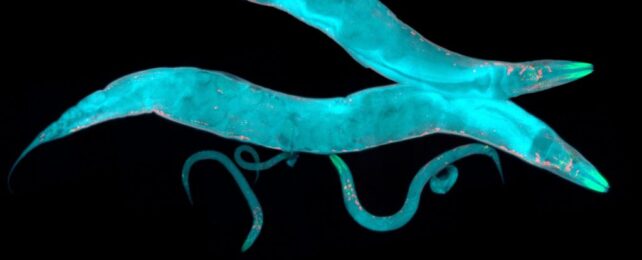

One of the most studied organisms on Earth has a nose for danger that scientists are just beginning to understand.

The mere whiff of dangerous bacteria is enough to put the immune system of a roundworm on high alert.

Like humans smelling 'off' food from the fridge, the olfactory neurons of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, may serve as an early warning sign for bad food.

Instead of stopping the worm from eating the pathogen, however, the stink of harmful bacteria prepares the worm's gut for the worst.

Before the food is gobbled up, the worm's intestinal cells begin destroying energy-producing organelles called mitochondria.

These cellular 'powerhouses' contain a bunch of iron, which most invading bacteria need to carry out a successful infection. By removing mitochondria from their intestinal cells, the worm's body is hindering a future infection from taking root.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley suspect that the pre-emptive response evolved to protect nematodes from lethal pathogens.

C. elegans needs to eat bacteria to survive, but knowing which cells are nutritious and edible and which are potentially harmful is crucial to the worm's survival.

Without specialized eyes, one of the only ways for the nematode to tell if a meal is dangerous before swallowing it is to detect the 'smell' of toxic bacteria.

It does this via the natural byproducts shed by bacteria into the environment, called volatile metabolites.

A bacteria that kills C. elegans, called Pseudomonas aeruginosa, produces a metabolite called acetylpropionyl.

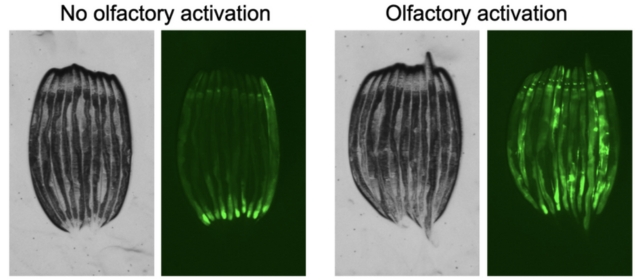

In experiments, the olfactory nervous system of roundworms was able to detect acetylpropionyl, and when it did, it triggered a mitochondrial stress response in the worm's cells, which was particularly detected in intestinal cells with staining.

These olfactory neurons are in constant 'lookout' mode when there's no odorant detected, becoming silenced when they detect an odorant. So when the scientists silenced the olfactory neurons, the worms' cells remained in a state of pre-emptive immune response, regardless of the presence of an odorant.

"The novelty is that C. elegans is getting ready for a pathogen before it even meets the pathogen," says neuroscientist Julian Dishart.

"There's also evidence that there's probably a lot more going on in addition to this mitochondrial response, that there might be more of a generalized immune response just by smelling bacterial odors."

Whether that extends to other animals with even stronger olfactory nervous systems is unknown.

Dishart thinks that because olfaction is conserved in other animal lineages, "it's totally possible that smell is doing something similar in mammals as it's doing in C. elegans."

Further research is needed to investigate if smells can prime the guts of other animals in a similar way.

"Is there actually a smell coming off of pathogens that we can pick up on and help us fight off an infection?" wonders neuroscientist Andrew Dillin.

"We've been trying to show this in mice. If we can actually figure out that humans smell a pathogen and subsequently protect themselves, you can envision down the road something like a pathogen-protecting perfume."

The study was published in Science Advances.