Scientists are pondering what might be called the volcanic solution to global warming. It would be the ultimate desperate measure, a climatological Hail Mary and, possibly, a very bad idea.

The only reason it's an actual subject of research is that human civilization has failed to take steps to stave off dangerous levels of climate change.

In 1991, Mount Pinatubo erupted in spectacular fashion. The ash fall and lahars killed hundreds of people in the central Luzon region of the Philippines.

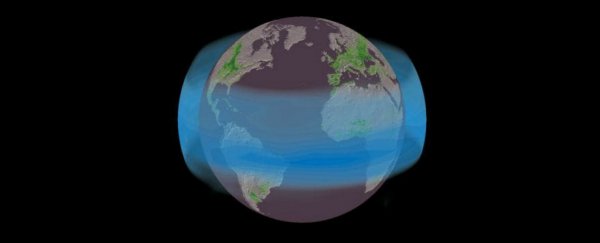

Molten-hot ash and gas shot into the upper atmosphere, spread out across the globe, reflected sunlight and naturally cooled the planet for more than a year. Researchers say nature may be offering an example of a possible technique for limiting global warming.

People can't command volcanoes to erupt, but they can more or less mimic the effects of a volcano through technology.

The basic idea is to use aircraft, or some other means, to spew sunlight-reflecting aerosols into the stratosphere and change the albedo - the reflectivity - of the planet. It goes by many names: solar geoengineering, solar radiation management, albedo management, albedo hacking.

One hypothesized reason for doing something so audacious is that it might benefit agriculture by preventing heat stress on food crops.

But a paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature came to a different and surprising conclusion. Using historical data from two volcanic eruptions, the researchers concluded that tampering with the atmosphere would have no net effect on crop yields.

The food crops wouldn't suffer as much heat stress as they would without the intervention in the atmosphere, but they also wouldn't receive as much photosynthesis-powering sunlight. The pluses would be offset by the minuses.

"If we think of geoengineering as experimental surgery, our findings suggest that the side effects of treatment are as bad as the original disease," said Jonathan Proctor, an agricultural economist at the University of California at Berkeley and the lead author of the paper.

But David Keith, a professor of applied physics at Harvard University who was not involved in the new research, said the paper by Proctor and his colleagues should not be interpreted as evidence that solar geoengineering is a bad idea.

"Reducing crop damage is but one of many reasons why geoengineering might make sense as a tool to limit climate risks in conjunction with emissions cuts," Keith wrote in an email.

"There are - of course - also many reasons why solar geoengineering may not make sense. Too risky. Too hard to govern. Etc."

He said there's a difference between solar geoengineering and volcanic eruptions. Solar geoengineering would not involve a one-time pulse of material in a single location but rather would be a continuous operation in many places.

No one is preparing to inject aerosols into the stratosphere. Scientists and political leaders don't know nearly enough about the consequences, good and bad, intended and unintended, of such an effort.

The technology doesn't even exist yet. Planes that spew sulfur dioxide exist only in PowerPoint presentations.

There's also the non-trivial question of who, exactly, has the authority and responsibility for changing the sky everywhere on Earth.

The planet has seen a rise in nationalism and a fraying of partnerships. President Trump has repeatedly attacked trade agreements and pushed a more isolationist agenda, and he has a history of calling global warming a hoax.

Albedo modification would not be a one-shot deal. It would have to be done constantly. Human civilization continues to pump increasing amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

The Paris climate agreement, signed by nearly 200 countries in 2015, commits nations to lowering their emissions, but compliance is questionable and Trump has said he will pull the United States out of the accord as soon as that is legally possible, in 2020.

If and when aerosols are pumped into the atmosphere, by a volcano or some technological gambit, they do not stay there forever. Much of that material migrates to polar latitudes and gradually coalesces into bigger droplets before falling to Earth.

To replenish the supply of sunlight-blocking aerosols, future generations would have to be fully committed to the project without interruption. Otherwise the planet's temperature would spike virtually overnight.

"If there is a sudden termination, then it's like being hit by a heat wave without having made the adaptations," said Raymond Pierrehumbert, a University of Oxford climate physicist.

Three years ago, the National Research Council of the National Academies of Sciences released a report saying that albedo modification is far too risky to attempt at this time.

The authors of the report concluded that any intervention in Earth's climate "should be informed by a far more substantive body of scientific research, including ethical and social dimensions, than is presently available."

"We haven't researched it adequately," Marcia McNutt, president of the National Academies, said this week in an interview with The Washington Post.

"There have been models done. There just haven't been any field experiments done to anyone's satisfaction."

She said that efforts to mitigate climate change have been too feeble and that it's past time to understand what options we have in a rapidly warming world.

"It's too late to wait," she said. "We can't be this seriously far down the global-warming curve and not be ready to do something about it."

There might be other benefits or harms from albedo modification. Proctor and his co-authors looked at only one economic sector: food crops.

What's unique about this research is that it's based on nature's own experiments with albedo modifications - the two big volcanic eruptions in the past 40 years that had enough oomph to change the global climate.

The first was in 1982, when El Chichon erupted in Mexico. The second was Pinatubo nine years later.

The researchers had reason to expect a different result, because the scientific literature previously has suggested that crop yields would benefit from stratospheric aerosols.

The tiny particles scatter sunlight and create more diffuse light at ground level. Such diffuse light can penetrate beneath a forest canopy and reach leaves on a plant normally heavily shaded on a sunny day.

But Proctor and his colleagues examined crop yield reports from around the globe and found that soy, wheat, rice and corn yields dropped after Pinatubo's eruption, with corn - which is more responsive to direct rather than diffuse sunlight - affected the most.

The researchers used this information to estimate the effects on crop yields in 2050 if albedo modification is used in an attempt to limit global warming.

"In all of this, there are many, many more unknowns than knowns," Proctor said. "The goal is to chip away at these unknowns one at a time."

Another form of geoengineering would involve directly removing carbon from the atmosphere. This includes capturing carbon as it is emitted at smokestacks and sequestering it underground.

The technologies for doing this are immature and limited by cost, the National Research Council found in 2015, but could be part of a portfolio of responses to global warming.

By contrast, albedo modification is relatively cheap, in theory. It might be done with a large fleet of planes flying at something like 70,000 feet.

The fuel in the planes could be modified to burn a high percentage of sulfur, though the planes would probably use special furnaces to burn sulfur and spew it into the air, Pierrehumbert said.

Such a system would require, among other things, public acceptance of the idea of using air pollution to fight global warming

"It's just barking mad," Pierrehumbert said. "It's just a lunatic idea to think that this is a good thing to have in our portfolio of responses to global warming."

A better idea, said Alan Robock, a climate scientist at Rutgers University, is to stop pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

"We all know the solution to global warming is - stop using the atmosphere as a sewer for our greenhouse gases," he said.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.