It might sound like a tall tale, but in very rare cases, humans can be born with boneless rear-end appendages, sometimes up to 18 centimeters long.

To date, official records have tallied about 40 babies born with 'true tails', consisting of soft, boneless, finger-like protrusions that are easily removed via surgery.

Nevertheless, the rare case studies tend to generate "an unusual amount of interest, excitement and anxiety", according to researchers. Often, this is because the 'tails' are conisidered to be benign, evolutionary remnants of a long lost ancestor.

As it turns out, that's based on an outdated theory that has been contentious for decades now. The reality for these children may be much darker, and they deserve medical attention, not our morbid fascination.

The appendages some babies are born with have historically been deemed 'true' or 'vestigial' tails. But that's a bit of a misnomer, as they aren't really like any other tail known in nature. They typically don't contain bones, cartilage, or a spinal cord. They just kind of hang there without a clear function.

Still, that doesn't mean these appendages are as harmless as scientists used to think.

The misunderstanding over the tail's origin starts with Charles Darwin himself. Over a century ago, Darwin proposed that human vestigial tails are evolutionary accidents, or rudimentary leftovers from a primate ancestor that was once tailed itself.

In the 1980s, scientists took this theory and ran with it. They argued that a genetic mutation, evolved by humans to erase our tails, could sometimes revert back to its ancestral state.

In 1985, a seminal paper defined two different types of 'tails' that human babies can be born with. The first, as mentioned before, is a vestigial or true tail, originally thought to be inherited from our ancestors.

But another type of outgrowth from the tailbone, which sometimes does include bone, is known as a 'pseudotail'.

Historically, the pseudotail has been the one associated with birth defects, and as such, it is not considered vestigial.

As it turns out, both rare appendages probably represent an incomplete fusion of the spinal column, or what's known as a spinal dysraphism. This suggests their formation is not a harmless 'regression' in the evolutionary process but a concerning disturbance in an embryo's growth most likely resulting from a mix of genetic and environmental factors.

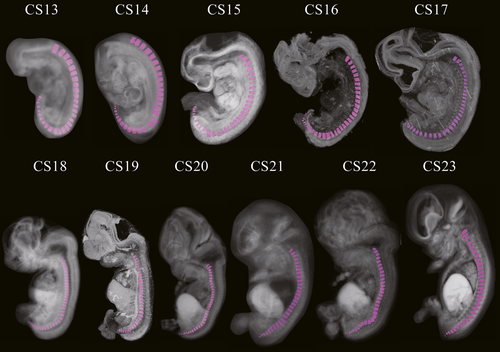

When a human embryo reaches about five weeks of development, it sprouts a tail-like structure composed of a neural tube and notochord, which is kind of like an early spinal cord.

By the eighth week of development, this tail is typically reabsorbed back into the embryo's body. If it sticks around until birth, it could indicate the presence of a larger birth defect.

In fact, human babies that are born with tails tend to have serious associated neurological defects. In 2008, for instance, a paper argued that "true vestigial tails are not benign" because they may be associated with underlying dysraphism.

Roughly half of the cases reviewed were associated with either meningocele or spina bifida occulta.

This suggests babies born with tails need greater medical attention than a simple surgery. And it strongly disagrees with the 1985 paper that argued "the true human tail is a benign condition not associated with any underlying [spinal] cord malformation."

In fact, as far back as 1995, researchers were arguing that babies born with both 'true' and 'pseudo' tails should undergo neuroimaging as well as surgery to make sure their development was tracking like it should.

So why have vestigial tails been reported in case studies since as though they were innocent, undisputed consequences of our genetic heritage?

Part of the problem is that it is not yet known if a true tail is directly derived from the embryonic tail, as some scientists have suggested. There simply isn't enough research on where the congenital abnormality lies – partly because of how rare these case studies are.

Regardless of where a baby's tail came form, however, evidence strongly suggests it is the result of a congenital issue and is not a harmless vestigial trait.

For the life and health of these children, that's an important message that needs to be cleared up once and for all.