For many elderly folk diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, not all is as it would appear. A distinct form of late-onset dementia called LATE could be the real cause of their condition. The problem is, telling the two apart is far from easy.

Recently published guidelines could help clinicians distinguish the two diseases, providing individuals with either of the conditions a better prognosis of their future mental health, while promoting awareness of diverse forms of dementia.

With so much focus on Alzheimer's in recent years, it's easy to forget that there are other neurodegenerative conditions to look out for.

Some are relatively easy to identify based on patient history, various biomarkers, or distinctive symptoms.

One particular form of dementia called limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy – or LATE for short – behaves uncannily like Alzheimer's disease, providing plenty of opportunity for mistaken diagnoses.

"Recent research and clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease have taught us two things," says Nina Silverberg, director of the Alzheimer's Disease Centres Program at the US National Institute on Ageing.

"First, not all of the people we thought had Alzheimer's have it; second, it is very important to understand the other contributors to dementia."

While the condition's name is new, LATE has been on the radar for a while now.

Researchers first noticed a strange stiffening of tissues in the hippocampus regions of dementia patients back in the mid-1990s. Alzheimer's is typically associated with messes of proteins in the form of tangled strings of tau and clumps of beta amyloid inside neurons. Yet the autopsied brains of these patients showed no signs of such accumulations.

More than a decade later, a culprit in the form of a protein called TDP-43 was discovered.

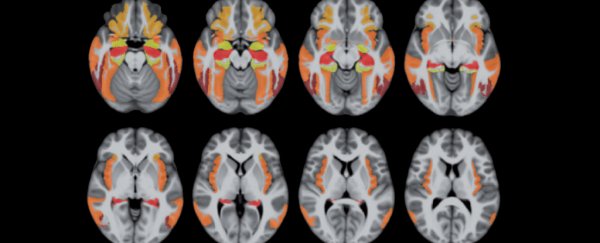

Away from its usual spot in the nucleus and burdened with phosphorus, the pathological form of the protein appeared to cause a whole lot of trouble in specific areas of the brain associated with memory and emotion.

This is by no means a rare event, either. Autopsies suggest anywhere from 20 to 50 percent of all people over the age of 80 might accumulate enough errant TDP-43 proteins to be cognitively affected.

As common as it might be in older demographics, the consequences look just like Alzheimer's disease, marked by a decline in recollection and deterioration in thinking and social skills.

Telling the two apart without performing an autopsy is no easy feat, especially without an agreed set of criteria. What's more, having one form of dementia doesn't exclude the other. Those with both Alzheimer's and LATE could suffer a double dose of symptoms.

"Noting the trend in research implicating TDP-43 as a possible Alzheimer's mimic, a group of experts convened a workshop to provide a starting point for further research that will advance our understanding of another contributor to late life brain changes," says Silverberg.

As a result of that workshop, clinicians now have a proposed set of criteria that could be used to tell LATE apart from Alzheimer's disease, as well as a bunch of recommendations on where researchers should look next.

Differences are still rather subtle, including contrasting patterns of various neurocognitive test scores and differences in rates of decline.

Unfortunately none of those criteria include anything as simple as a blood-test. As nice as it would be, finding a convenient biomarker for either condition is still on the 'to-do' list.

But researchers have identified some genes to watch out for, a number of which seem to coincide with genetics that play a role in both diseases.

Having a way to separate the conditions could be a major win for researchers investigating promising therapies for Alzheimer's disease, who have been confounded by a string of failures in recent years.

Not only could we be wrong about many of our basic assumptions on the disease, we might also be carrying out clinical trials on patients with an incorrect diagnosis.

Dementia is set to be a growing problem in a world with an ageing population; a disease that is proving far more complex than would first appear. Unravelling that complexity is a necessary step in finding the best course of action to help people.

This research was published in Brain.