Researchers have discovered what they describe as 'bacterial vampirism', identifying particular types of bacteria that are attracted to human blood – an attraction that can lead to fatal infections.

The team from Washington State University and the University of Oregon outlines how these deadly bacteria are drawn to serum – the liquid part of our blood – because of the nutrients and energy it provides.

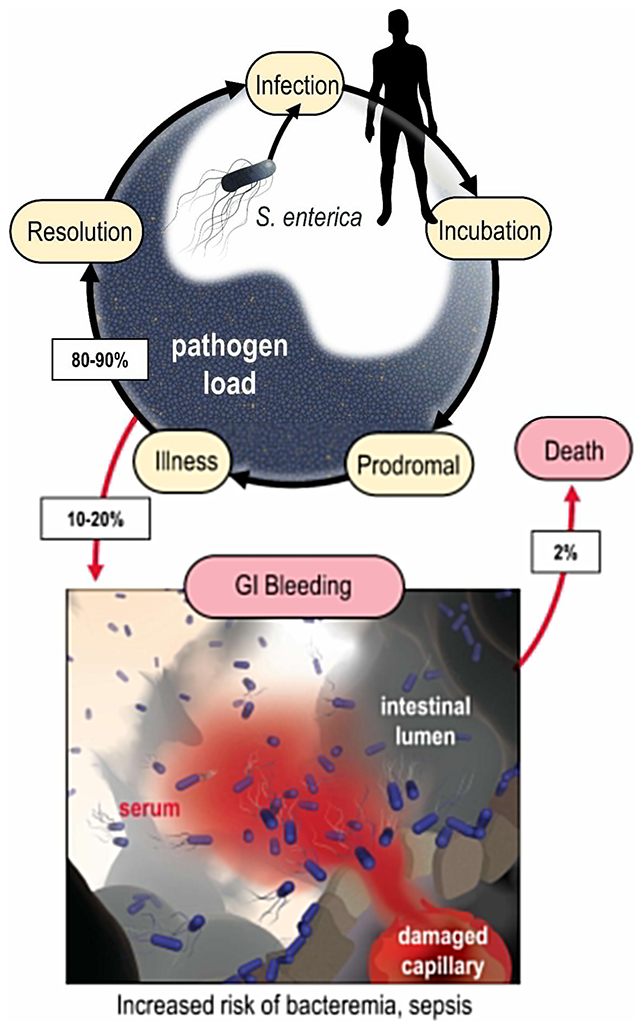

That can be a particular problem for people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where intestinal bleeding can offer gut bacteria a route into the bloodstream. However, these findings also shed light on potential new treatment routes.

"Bacteria infecting the bloodstream can be lethal," says microbiologist Arden Baylink from Washington State University. "We learned some of the bacteria that most commonly cause bloodstream infections actually sense a chemical in human blood and swim toward it."

The researchers used a customized device for injecting tiny amounts of fluid and a high-powered microscope to analyze the interaction of bacteria and blood.

Strains of three bacteria known to cause fatal infections, belonging to the species Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli, and Citrobacter koseri, were found to be attracted to the human serum.

What's more, the team identified some of the biological interactions: it looks as though the amino acid serine is one of the chemicals the bacteria can sense, seek out, and consume, via particular protein receptors.

This response doesn't take long at all either. In the experiments run for the study, it took less than a minute for these types of bacteria to realize that blood was nearby and to head towards it.

"We show here that the bacterial attraction response to serum is robust and rapid," write the researchers in their published paper.

The types of bacteria investigated here, from the family Enterobacteriaceae, have already been linked to conditions such as gastrointestinal bleeding and sepsis, particularly where IBD is involved.

The thinking is that these bacteria are latching on to the internal bleeding that often comes with IBD, which is how fatalities can occur. About 1.3 percent of the population of the US, some 3.1 million people, are thought to have IBD, which can then lead to other chronic diseases and health complications.

Knowing more about how bacteria sense the serum in blood, and make use of it, might eventually save lives if treatments are focused on this – though cloves of garlic and stakes to the heart aren't likely to be involved.

"By learning how these bacteria are able to detect sources of blood, in the future we could develop new drugs that block this ability," says immunologist Siena Glenn, from Washington State University.

"These medicines could improve the lives and health of people with IBD who are at high risk for bloodstream infections."

The research has been published in eLife.