Could nature's smallest organisms help us to combat rising CO2 levels and even oil spills?

Strange as it might seem, the answer might be yes, with research into newly discovered deep-sea microbes suggesting these tiny critters possess a keen appetite for pollutants.

The microbes – collected in the Gulf of California, around 2,000 metres (6,562 feet) below the surface of the water – live in conditions where subterranean volcanic activity increases temperatures to around 200 degrees Celsius (392 degrees Fahrenheit).

In the new study, a total of 551 separate genomes were identified – including 22 that had never been recorded before – and the microorganisms were observed harvesting hydrocarbons such as methane and butane as life-giving energy sources.

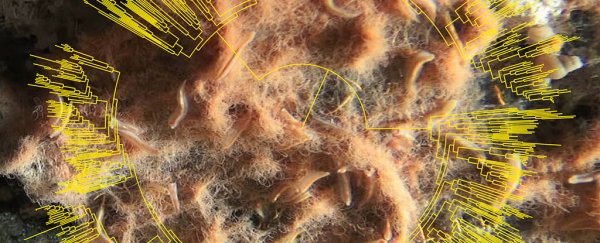

View of the seafloor (Brett Baker/University of Texas at Austin)

View of the seafloor (Brett Baker/University of Texas at Austin)

"This shows the deep oceans contain expansive unexplored biodiversity, and microscopic organisms there are capable of degrading oil and other harmful chemicals," says lead researcher and marine scientist Brett Baker from the University of Texas at Austin.

"Beneath the ocean floor huge reservoirs of hydrocarbon gases – including methane, propane, butane and others – exist now, and these microbes prevent greenhouse gases from being released into the atmosphere."

Not only are they keeping harmful gases from escaping, they could be helpful in limiting or cleaning up pollution in the future, if their abilities can be harnessed or copied. It's still early days in the study of these miniature beings, but the way that they feed off hydrocarbons is notably unusual.

Indeed, the 22 new types of microbe are so genetically different from anything we've seen before, they look to represent a new branch on the tree of life that scientists use to chart out all living creatures.

But that's not surprising, considering it's estimated that 99.9 percent of the world's microbes can't yet be reproduced in a lab, meaning there are still probably zillions of new life forms like this for scientists to discover and try to understand.

"The tree of life is something that people have been trying to understand since Darwin came up with the concept over 150 years ago, and it's still this moving target at the moment," says Barker.

Thanks to improvements in DNA sequencing and computer software though, that moving target is coming into clearer focus as the years go by. The microbes discovered in this study can improve our understanding of biology as well as – potentially – keep a lid on pollutants in the environment.

Also notable is the craft that was used to collect the microbes: the Alvin submersible, the same vehicle that explored the submerged Titanic wreckage in 1986.

More research and a greater range of samples are going to be needed to get a full picture of how these deep-sea microbes operate, and what part they might play in the carbon cycle. For now though, there's plenty to pique the interests of scientists in these findings.

"We think that this is probably just the tip of the iceberg in terms of diversity in the Guaymas Basin," says Baker.

"So, we're doing a lot more DNA sequencing to try to get a handle on how much more there is. This paper is really just our first hint at what these things are and what they are doing."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.