As the coronavirus pandemic drags on, subsequent waves of infections are reaching staggering new heights, and more people are losing loved ones. Regardless of how each country has chosen to meet this challenge, economies are struggling, causing businesses to fail and taking away people's livelihoods.

Our world is screaming out for a vaccine like never before.

But now a group of researchers have warned that at least four of the current batch of potential vaccines undergoing clinical trials involve a component that might increase people's risk of contracting HIV.

One of these vaccine candidates passed its phase 2 trial in August and is about to undergo a large phase 3 study in Russia and Pakistan.

The warning comes from a team of scientists led by Susan Buchbinder, a University of California San Francisco professor who runs the HIV Prevention Research in the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

The team experienced a similar issue first-hand while trying to develop a vaccine for HIV.

To their dismay their most promising candidate after 20 years of research backfired, leaving some patients even more vulnerable to the disease. They shared their 'cautionary tale' in The Lancet.

"We are concerned that use of an Ad5 vector for immunisation against SARS-CoV-2 could similarly increase the risk of HIV-1 acquisition among men who receive the vaccine," they wrote.

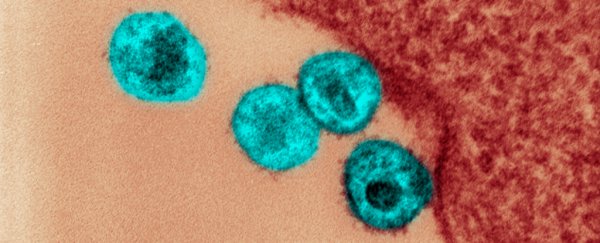

Vaccines require a vehicle of sorts to deliver them to their required locations. This is called a vector and it is this component of the vaccine that is causing some concern.

Several coronavirus vaccine candidates are using adenoviruses as these vectors. For example, in one trial a genetically modified adenovirus is being used to deliver the gene code of the coronavirus spike proteins, so that our immune system can learn to recognise the spike, and therefore SARS-COV-2, as an invader

Adenoviruses are usually harmless aside from causing colds, and other vaccines have successfully used different modified versions of them as vectors without any evidence of increased risk of HIV.

But four coronavirus candidate vaccines are using a vector called Ad5 (recombinant adenovirus type-5), and it was this that caused problems in the HIV vaccine.

A decade ago, when Buchbinder and her colleagues tried to do something similar to protect against HIV, two trials led to men having an increased risk of catching HIV, particularly if they had already been infected with Ad5 in the past.

While the mechanism behind this is still unclear, one 2008 study suggests it may have something to do with increased activation of the immune system providing HIV with more cells to target.

In 2014, a review led by immunologist Anthony Fauci, Director of NIAID, recommended caution when using this vector in vaccines for regions with HIV prevalence.

"This important safety consideration should be thoroughly evaluated before further development of Ad5 vaccines for SARS-CoV-2," The Lancet correspondence concludes.

But companies developing these vaccines have said they're aware of this problem and taking the risks into account.

One company, ImmunityBio, told Science their Ad5 vector has been genetically 'muted' to decrease the level of immune response it triggers. If all goes well with their California trial they hope to test it in South Africa next.

Head of the South African Medical Research Council Glenda Gray who worked on the HIV vaccines with the authors of The Lancet correspondence explains just avoiding this vector may not be the best solution.

"What if this vaccine is the most effective vaccine?" she asked Science, saying that each country's experts must be allowed to make their own decision.

The good news is, the scientific community is discussing this risk, and this is the type of adverse reaction that trials can help to find out.

Once vaccines have passed through clinical trials they have an incredible record for being very safe. In the case of Buchbinder's HIV vaccine, this vigorous testing process worked as it should to pick up the problems with the vaccine before it was released.

Teams of researchers around the world are working hard to ensure this is also being applied in the development of a COVID-19 vaccine. So far several vaccine trials have been paused for reassessment over safety concerns.

Hopefully not all trials will be met with such issues. The whole world is watching closely.

You can read the full correspondence published in The Lancet here.