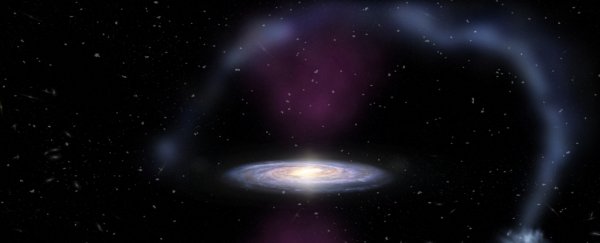

The centre of the Milky Way galaxy is a relatively calm place now (compared to other galactic centres), but that hasn't always been the case. In fact, just 3.5 million years ago, it was positively riotous - expelling a burst of energy that eventually blasted 200,000 light-years above and below the galactic plane.

The shockwaves of this colossal flare - called a Seyfert flare - can be observed today in the Magellanic Stream, a high-velocity stream of gas extending from the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, 200,000 light-years from the Milky Way.

It's so powerful, astronomers believe it could only have come from Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. Because the first evidence for the flare was published in 2013, they have named the event BH2013.

(James Josephides/ASTRO 3D)

(James Josephides/ASTRO 3D)

In 2013, astrophysicist Joss Bland-Hawthorn of the University of Sydney and the ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D) and colleagues estimated that the event occurred between 1 and 3 million years ago.

Now, more observations taken using the Hubble Space Telescope - and therefore a bigger dataset - have provided even more compelling evidence for the event. And the team has been able to narrow down a timeframe for both when the event occurred, as well as its duration.

"These results dramatically change our understanding of the Milky Way," said astronomer Magda Guglielmo of the University of Sydney.

"We always thought about our Galaxy as an inactive galaxy, with a not-so-bright centre. These new results instead open the possibility of a complete reinterpretation of its evolution and nature."

There are several clues that have helped put together the picture. The clearest are the enormous 'Fermi bubbles' of gamma- and X-ray radiation, extending above and below the galactic plane, detected by both the Fermi and ROSAT satellites. These bubbles extend, in total, about 50,000 light-years - 25,000 above and 25,000 below the galactic plane.

Then, in 2013, astronomers reported the discovery of hydrogen-alpha emission along a section of the Magellanic Stream directly in line with the bubble. The most likely explanation for this, they explained, was a burst of ionising energy from the centre of the Milky Way.

What Hubble has spotted is another piece of that puzzle. Some absorption ratios in ultraviolet wavelengths reveal that some of the clouds in the Stream are highly ionised, and by a very energetic source.

"We show how these are clouds caught in a beam of bipolar, radiative 'ionisation cones' from a Seyfert nucleus associated with Sgr A*," the researchers wrote in their paper.

Basically, two expanding cones, starting from a small region close to the galactic centre and expanding outwards above and below the galactic plane, blasted ionising radiation so far into space, it ionised the gas in the Magellanic Stream, hundreds of thousands of light-years away.

"The flare must have been a bit like a lighthouse beam," Bland-Hawthorn said. "Imagine darkness, and then someone switches on a lighthouse beacon for a brief period of time."

A schematic diagram of the ionizing radiation field over the south galactic hemisphere, disrupted by the flare. (Bland-Hawthorne, et al./ASTRO 3D)

A schematic diagram of the ionizing radiation field over the south galactic hemisphere, disrupted by the flare. (Bland-Hawthorne, et al./ASTRO 3D)

Nothing else except the relativistic jets from an actively feeding black hole could be powerful enough to produce that effect, the researchers said.

The flare took place around 3.5 million years ago, and lasted for about 300,000 years. That's a pretty short blast on the cosmic scale.

Here on Earth, it was already the Pliocene, the period in which most modern species emerged.

And although it seems Sgr A* has been relatively quiet in the intervening years, recent observations show that it could be stirring.

"This is a dramatic event that happened a few million years ago in the Milky Way's history," said astronomer Lisa Kewley of the Australian National University and the ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3D.

"A massive blast of energy and radiation came right out of the galactic centre and into the surrounding material. This shows that the centre of the Milky Way is a much more dynamic place than we had previously thought."

Our 26,000 light-year distance from the galactic centre means we're likely safe from any giant flares - after all, we seem to have emerged unscathed from BH2013. If we're lucky, though, we might get to see one heck of a light show.

The research has been accepted into The Astrophysical Journal and a draft version is available here.