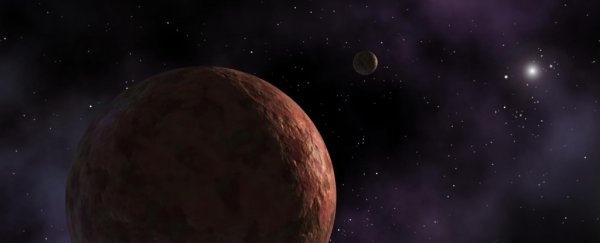

Somewhere in the outer reaches of the Solar System, beyond the orbit of Neptune, something wonky is happening. A few objects are orbiting differently from everything else, and we don't know why.

A popular hypothesis is that an unseen object called Planet Nine could be messing with these orbits; astronomers are avidly searching for this planet. But physicists have recently come up with an alternative explanation they think is more plausible.

Instead of one big object, the orbital wobblies could be caused by the combined gravitational force of a number of smaller Kuiper Belt or trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). That's according to astrophysicists Antranik Sefilian of the University of Cambridge in the UK and Jihad Touma of the American University of Beirut in Lebanon.

If it sounds familiar, that's because Sefilian and Touma are not the first to think of this idea - but their calculations are the first to explain significant features of the strange orbits of these objects, while taking into account the other eight planets in the Solar System.

A hypothesis for Planet Nine was first announced in a 2016 study. Astronomers studying a dwarf planet in the Kuiper Belt noticed that several TNOs were "detached" from the strong gravitational influence of the Solar System's gas giants, and had weird looping orbits that were different from the rest of the Kuiper Belt.

But the orbits of these six objects were also clustered together in a way that didn't appear random; something seemed to have tugged them into that position. According to modelling, a giant, heretofore unseen planet could do so.

So far, this planet has remained elusive - not necessarily odd, since there are considerable technical challenges to seeing a dark object that far away, especially when we don't know where it is. But its evasiveness is prompting scientists to seek alternative explanations.

"The Planet Nine hypothesis is a fascinating one, but if the hypothesised ninth planet exists, it has so far avoided detection," Sefilian said, adding that the team wanted to see if there was a less dramatic explanation of the weird TNO orbits.

"We thought, rather than allowing for a ninth planet, and then worry about its formation and unusual orbit, why not simply account for the gravity of small objects constituting a disk beyond the orbit of Neptune and see what it does for us?"

The researchers created a computer model of the detached TNOs, as well as the planets of the Solar System (and their gravity), and a huge disc of debris past Neptune's orbit.

By applying tweaks to elements such as the mass, eccentricity and orientation of the disc, the researchers were able to recreate the clustered looping orbits of the detached TNOs.

"If you remove Planet Nine from the model, and instead allow for lots of small objects scattered across a wide area, collective attractions between those objects could just as easily account for the eccentric orbits we see in some TNOs," Sefilian said.

This solves a problem that scientists from the University of Colorado Boulder had when they first floated the collective gravity hypothesis last year. Although their calculations were able to account for the gravitational effect on the detached TNOs, they couldn't explain why their orbits were all tilting the same way.

And there's still another problem with both models: in order to produce the observed effect, the Kuiper Belt needs a collective gravity of at least a few Earth masses.

Current estimates, however, put the mass of the Kuiper Belt at just 4 to 10 percent of Earth's mass.

But, according to Solar System formation models, it should be much higher; and, Sefilian notes, it's hard to view the entirety of a debris disc around a star when you're inside it, so it's possible that there's a lot more to the Kuiper Belt than we're able to see.

"While we don't have direct observational evidence for the disc, neither do we have it for Planet Nine, which is why we're investigating other possibilities," Sefilian said.

"It's also possible that both things could be true - there could be a massive disk and a ninth planet. With the discovery of each new TNO, we gather more evidence that might help explain their behaviour."

The team's research is due to appear in the Astronomical Journal and you can find the pre-print on arXiv.

A version of this article was first published in January 2019.