Contrary to popular belief, it's not possible for you to swallow your own tongue. If you're a human, at least. It turns out toads actually do it on purpose every time they eat.

"We know a lot about how frogs extend their tongues and how it sticks to their prey, but prior to this study, essentially everything that happens after they close their mouths was a mystery," says University of Florida herpetologist Rachel Keeffe.

So Keeffe and colleagues used high-speed X-ray videos to work out what was happening when these amphibians slam their mouths shut around a meal, and the results were completely unexpected.

"We weren't sure what was happening at first," says Keeffe. "The whole floor of the mouth was pulled backward into the throat and the tongue along with it."

It took months of carefully studying the cane toads (Rhinella marina) as they ate hundreds of crickets (Gryllodes sigillatus) and creating 3D animations to puzzle out this bizarre feeding mechanism.

Frogs are well known for capturing their prey with fast, sticky tongues, but therein lies the problem their unusual anatomy had to solve: how to then pry the food from that clingy whip to send it down their guts.

From capture to swallowing, the whole process takes under two seconds, but there are a whole series of events happening within the toad during this short timeframe.

The team attached tiny metallic beads to the toad's tongue so they could track the muscle's movements in the x-ray footage. As shown in the video below, the orange marker at the tip of its tongue lashes out to snag an insect, then snaps back into the toad's mouth. But it doesn't stop there, continuing down the throat a whole 4.5 centimeters (1.8 inches), until it almost touches the toad's heart.

"The mean distance that the tongue stretches during retraction equals or exceeds the mean distance that it stretches during protrusion," the researchers write in their paper, explaining the tongue's maximum protrusion was 4.1 centimeters on average.

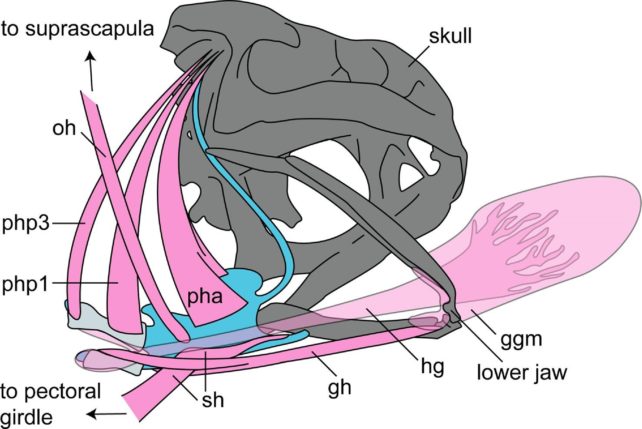

Here near their heart, the hyoid – a flexible cartilage plate suspended by strings of muscles – snaps shut against the tongue.

"The hyoid shoots up and presses the tongue against the roof of the mouth, after which it moves forward, essentially scraping the food off into the esophagus," explains Keeffe.

The hyoid (which some toads also use to make clicking calls) naturally seals the floor of the mouth while the toad is resting. But its connection to the tongue means it flings open as the muscle extends, opening wide as the toad gapes its mouth, ready for the tongue's snapback.

This is probably why toads and many frogs have strange ridges or bump-like 'teeth' on the roof of their mouths, Keeffe and team suspect; to aid with this food de-sticking. The hyoid markers hit this area with precision in the researchers' 3D reconstruction. The hyoid's flexibility would also help with its scraping task.

"Even if a toad repositions the tongue within the mouth during a double-swallow, the prey remains attached to the tongue throughout manipulation," Keeffe and colleagues write. This suggests the frogs need the hyoid mechanism to dislodge their food successfully.

The researchers are now keen to repeat these investigations to see if this tongue recoil and scrape feeding mechanism is universal across nearly 5,000 species of frog, amongst which there is a huge diversity of hyoid and tongue shapes.

This research was published in Organismal Biology.