A study of 26 years' worth of wolf behavioral data, and an analysis of the blood of 229 wolves, has shown that infection with the parasite Toxoplasma gondii makes wolves 46 times more likely to become a pack leader.

The research shows that the effects of this parasite in the wild have been horrendously understudied – and its role in ecosystems and animal behavior underestimated.

If you have a cat, you've probably heard of this parasite before. The microscopic organism can only sexually reproduce in the bodies of felines, but it can infect and thrive in pretty much all warm-blooded animals.

This includes humans, where it can cause a typically symptomless (but still potentially fatal) parasitic disease called toxoplasmosis.

Once it's in another host, individual T. gondii parasites needs to find a way to get their offspring back inside a cat if it doesn't want to become an evolutionary dead-end. And it has a kind of creepy way of maximizing its chances.

Animals such as rats infected with the parasite start taking more risks, and in some cases actually become fatally attracted to the scent of feline urine, and thus more likely to be killed by them.

For larger animals, such as chimpanzees, it means an increased risk of a run-in with a larger cat, such as a leopard. Hyenas infected with T. gondii also are more likely to be killed by lions.

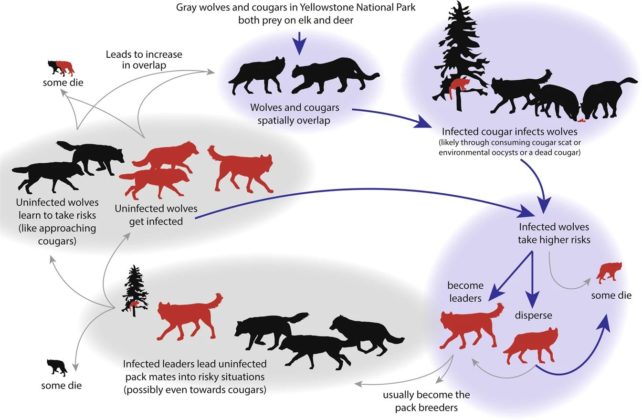

Gray wolves (Canis lupus) in the Yellowstone National Park aren't exactly cat prey. But sometimes their territory overlaps with that of cougars (Puma concolor), known carriers of T. gondii, and the two species both prey on the elk (Cervus canadensis), bison (Bison bison), and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) that also can be found there.

It's possible that wolves also become infected, perhaps from occasionally eating dead cougars, or ingesting cougar poo.

Data collected on the wolves and their behavior for nearly 27 years offered a rare opportunity to study the effects of the parasite on a wild, intermediate host.

The researchers, led by biologists Connor Meyer and Kira Cassidy of the Yellowstone Wolf Project, also took a look at blood samples from wolves and cougars to gauge the rate of T. gondii infection.

They found that wolves with a lot of territory overlap with cougars were more likely to be infected with T. gondii.

But there was a behavioral consequence, too, with significantly increased risk-taking.

Infected wolves were 11 times more likely to disperse from their pack, into new territory. Infected males had a 50 percent probability of leaving their pack within six months, compared with a more typical 21 months for the uninfected.

Similarly, infected females had 25 percent chance of leaving their pack within 30 months, compared with 48 months for those who weren't infected.

Infected wolves were also way more likely to become pack leaders. T. gondii may increase testosterone levels, which could in turn lead to heightened aggression and dominance, which are traits that would help a wolf assert itself as a pack leader.

This has a couple of important consequences. Pack leaders are the ones who reproduce, and T. gondii transmission can be congenital, passed from mother to offspring. But it can also affect the dynamics of the entire pack.

"Due to the group-living structure of the gray wolf pack, the pack leaders have a disproportionate influence on their pack mates and on group decisions," the researchers write in their paper.

"If the lead wolves are infected with T. gondii and show behavioral changes … this may create a dynamic whereby behavior, triggered by the parasite in one wolf, influences the rest of the wolves in the pack."

If, for example, the pack leader seeks out the scent of cougar pee as they boldly push into new territory, they could face greater exposure to the parasite, thus a greater rate of T. gondii infection throughout the wolf population. This generates a sort of feedback loop of increased overlap and infection.

It's compelling evidence that tiny, understudied agents can have a huge influence on ecosystem dynamics.

"This study demonstrates how community-level interactions can affect individual behavior and could potentially scale up to group-level decision-making, population biology, and community ecology," the researchers write.

"Incorporating the implications of parasite infections into future wildlife research is vital to understanding the impacts of parasites on individuals, groups, populations, and ecosystem processes."

The research has been published in Communications Biology.

An earlier version of this article was published in November 2022.