An expedition to the bottom of the Great Blue Hole off the coast of Belize in Central America has returned with a cargo of worrying information.

After studying a 30-meter (98-foot) sediment core extracted from the floor of the sinkhole, scientists discovered that tropical cyclones have increased in frequency over the last 5,700 years. This trend is not only going to continue – it's going to reach a fever pitch driven by a changing climate.

"A total of 694 event layers were identified. They display a distinct regional trend of increasing storminess in the southwestern Caribbean, which follows an orbitally driven shift in the Intertropical Convergence Zone," writes a team led by geoscientist Dominik Schmitt of Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany.

"A 21st-century extrapolation suggests an unprecedented increase in tropical cyclone frequency, attributable to the Industrial Age warming."

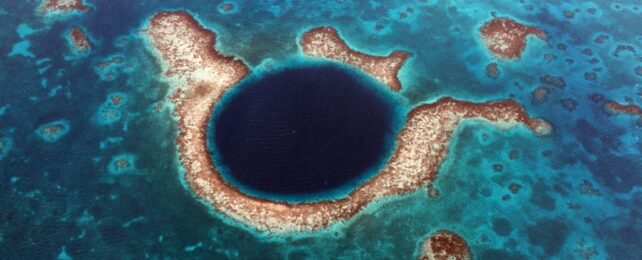

The Great Blue Hole at Belize is a popular destination for scuba divers, popularized by oceanographer Jacques Cousteau more than 50 years ago. At a depth of 124 meters, it plunges into the surrounding seafloor, its upper reaches a haven for marine life seeking protection from the wild vagaries of ocean weather.

There's another facet to this relative coziness; any sediment dumped within is likely to stay put. Layers of mineral deposited in sequence on the sinkhole floor serve as an excellent record of times past, recording major events like cyclones that churn up and dump new material into the Great Blue Hole.

"Due to the unique environmental conditions – including oxygen-free bottom water and several stratified water layers – fine marine sediments could settle largely undisturbed in the Great Blue Hole," Schmitt explains.

"Inside the sediment core, they look a bit like tree rings, with the annual layers alternating in color between gray-green and light green depending on organic content."

The extraction of a core sample is a delicate procedure that involves drilling into the seafloor and carefully removing a long, vertical, cylindrical section.

An analysis of that sediment involves identifying which layers were deposited by which processes. Violent events such as cyclones deposit layers with larger sediment grains than non-storm ocean processes, so it's a matter of carefully combing over the core and identifying those large-grained, differently-hued cyclone deposits.

"The tempestites stand out from the fair-weather gray-green sediments in terms of grain size, composition, and color, which ranges from beige to white," Schmitt says.

The Great Blue Hole of Belize started its life as a limestone cave underground, an origin alluded to by the huge stalactites that can still be found in its depths. It became a sinkhole during the last glacial period, when its roof collapsed, subsequently flooding the cavity with water and transforming it into the thriving marine ecosystem it is today.

The team's work involved carefully studying a core that covered the most recent 5,700 years of that history. In that timespan, the researchers identified 694 "event layers" that they attributed to tropical cyclones. With this data in hand, they were then able to piece together how cyclone frequency has changed over time

The core revealed a steady trend of increasing cyclone activity over the 5,700 years.

"A key factor has been the southward shift of the equatorial low-pressure zone," Schmitt says. "Known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone, this zone influences the location of major storm formation areas in the Atlantic and determines how tropical storms and hurricanes move and where they make landfall in the Caribbean."

But there were smaller-term fluctuations in cyclone frequency that, the researchers found, could be linked to warmer and cooler periods in Earth's climate timeline, with greater frequency occurring during warm periods.

Based on these trends, we could be facing an unprecedented spike in tropical cyclone activity. There were nine cyclone events in the last 20 years alone; a frequency that is inconsistent with normal, natural climate fluctuations.

"Our results suggest that some 45 tropical storms and hurricanes could pass over this region in our century alone," says biosedimentologist Eberhard Gischler of Goethe University Frankfurt. "This would far exceed the natural variability of the past millennia."

The team's research has been published in Science Advances.