SpaceX, the rocket company founded by Elon Musk, successfully launched its first five dozen Starlink telecommunications satellites on Thursday night.

If all goes according to plan in the coming weeks, the new fleet of experimental spacecraft may pave the way for a global, ultra-fast, and lucrative internet product, possibly within a couple of years.

"Starlink will connect the globe with reliable and affordable high-speed broadband services," SpaceX tweeted just before the launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida

SpaceX broadcast the inaugural Starlink mission, which launched aboard a Falcon 9 rocket at 10:30 p.m. ET. A little more than an hour after liftoff, the rocket's upper stage deployed all 30,000 pounds' (13,600 kilograms') worth of satellites at once – the heaviest payload SpaceX has ever launched. (Video of the manoeuvre is shown below.)

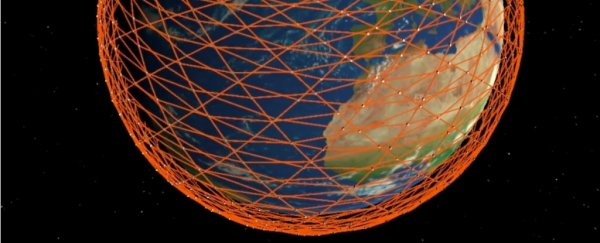

(Mark Handley/University College London)

(Mark Handley/University College London)

The spacecraft were released about 273 miles (440 kilometers) above Earth, somewhere over the Indian Ocean about halfway between Australia and Antarctica.

Musk previously described the deployment as an odd yet efficient way to get five dozen spacecraft off a rocket.

"This will look kind of weird compared to normal satellite deployments," Musk told reporters during a call on May 15.

When a rocket launches many satellites at once, typically a device at the top of the rocket's uppermost stage deploys them, one by one, with complex and heavy spring-loaded mechanisms. SpaceX launched one such mission in December, deploying a cornucopia of 64 satellites with one rocket.

But SpaceX eschewed that approach for an unusual one: It slowly spun the rocket's upper stage, then released its payload like an overhand baseball pitch – except instead of a baseball, it was the entire stack of flat-packed Starlink satellites.

"There are no deployment mechanisms between those spacecraft, so they really are slowly fanning out like a deck of cards into space," Tom Praderio, a SpaceX software engineer, said while hosting the mission's webcast.

Praderio quickly added: "You can kind of see one breaking away from the pack right now. Those spacecraft will slowly disperse over time."

The gif below shows the Starlink deployment 360 percent faster than it actually happened.

(SpaceX)

(SpaceX)

Big plans for Starlink's future

Each Starlink satellite is roughly the size of an office desk and weighs about 500 pounds (227 kilograms), comes with a single solar panel, and has antennas to shuttle data to and from the ground.

Each spacecraft has a weak yet highly efficient Hall thruster, or ion engine, that shoots out krypton gas. Musk said the engine would help each Starlink avoid other satellites, dodge known space junk (though experts are reasonably worried about the scheme), and – once it has neared the end of its useful life – deorbit and destroy itself.

Most immediately, the engines will help Starlink spacecraft slowly ascend to a higher orbit of 342 miles (550 kilometers) above Earth.

(SpaceX via Twitter)SpaceX's first 60 Starlink satellites lack a critical component, though: laser beams interlinks.

(SpaceX via Twitter)SpaceX's first 60 Starlink satellites lack a critical component, though: laser beams interlinks.

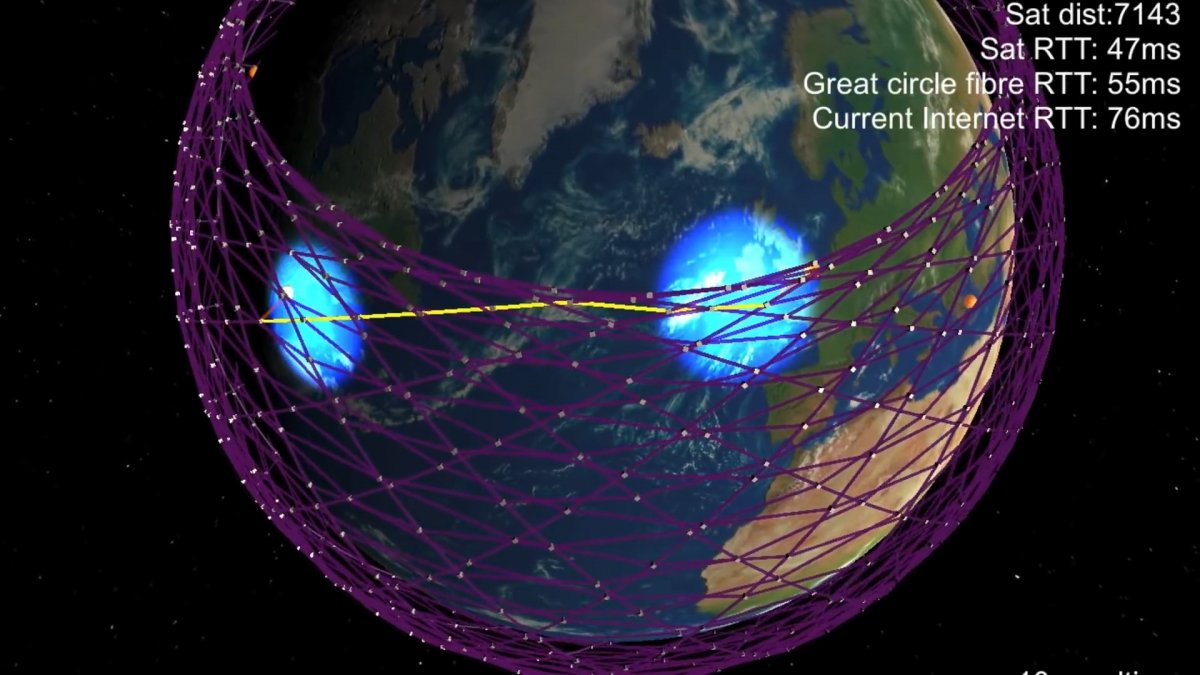

Each future spacecraft will use such lasers to connect to four other satellites, forming a robust mesh network above Earth meant to move internet traffic at close to the speed of light in a vacuum. (That's nearly 50% faster than fibre-optic cables can transmit data on the ground, and it would grant Starlink a huge advantage in cutting lag.)

With this first experimental batch, though, Musk said SpaceX would test the Starlink internet concept by routing data from one satellite to another through existing ground cables.

SpaceX's goal with Starlink is to launch up to 12,000 similar satellites – nearly seven times the number of operational spacecraft in orbit now – before a 2027 deadline established by the Federal Communications Commission. To achieve that amount, SpaceX would have to launch more than one Starlink mission a month over the next eight years.

But not nearly that many are required to make the concept work and bring global internet access.

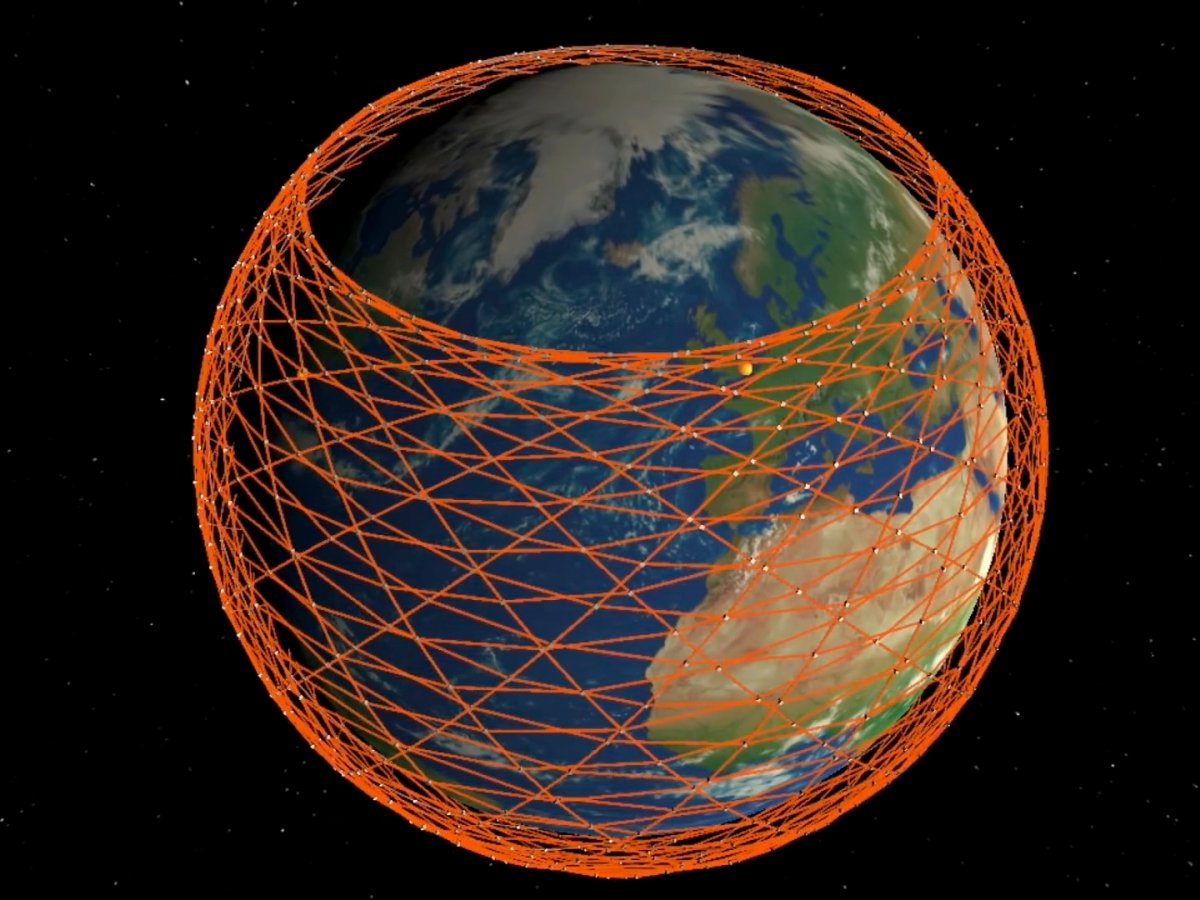

(Mark Handley/University College London)

(Mark Handley/University College London)

Musk said SpaceX had "sufficient capital" to get Starlink operational and suggested the Starlink project could start making money long before the full constellation maxed out.

"For the system to be economically viable, it's really on the order of 1,000 satellites," Musk said, "which is obviously a lot of satellites, but it's way less than 10,000 or 12,000."

The pervasiveness of the overhead satellites also means Starlink could bring almost lag-free broadband internet to most regions of Earth, as well as aeroplanes, ships, and even cars (perhaps Tesla electric vehicles to start). Musk has said multiple times that he'd like to make such internet access affordable, particularly in areas with little to no web service.

Mark Handley, a computer-networking researcher at University College London who has studied Starlink, previously told Business Insider that the project could affect the lives of "potentially everybody" by bringing high-speed and pervasive broadband to most parts of the world.

"This is the most exciting new network we've seen in a long time," Handley said.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: