As most new parents can attest, sleepless nights don't exactly make for the most cheerful mornings. This is why it makes little sense that total sleep deprivation temporarily resets the mood of nearly half of people with a major depressive disorder.

Brain scans on volunteers have shown why this might be the case, revealing intriguing changes between critical areas of the brain in healthy volunteers and those diagnosed with major depression.

Research led by the University of Pennsylvania in the US used functional MRI to map and measure the brain functions of 54 individuals without a history of psychiatric or mood disorders and 30 with major depression.

Of those without a history of depression, 16 were placed into a control group and given a good night's sleep between tests. For everybody else, with and without a diagnosis, it was one long evening of reading, playing computer games, watching television… and no shut-eye. No caffeine, no exercise. Just tedium until sunrise.

Deprived of sufficient time to rest and replenish, the human brain isn't the most efficient machine. A chunk of tissue at the front of our brain called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex chugs along slowly, making it harder to pay attention.

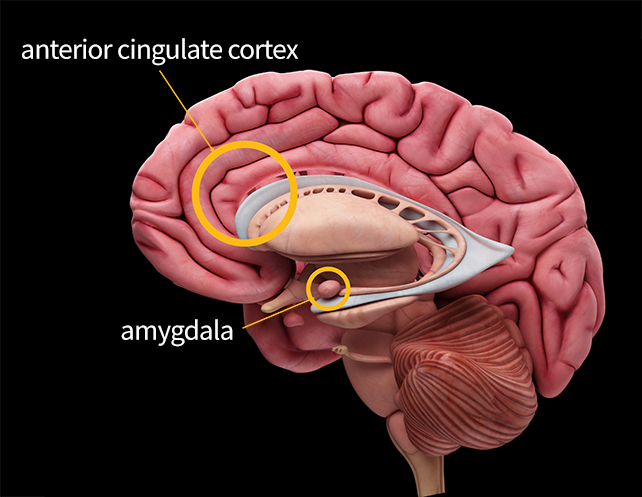

Not only is our cognition slowed, but so is our ability to regulate our emotions since the amygdala – a key component of the limbic system – works overtime, especially in response to negative stimuli. Without the prefrontal cortex to temper our thinking, we can become snappy and irritable.

Yet since the dawn of psychiatric research, sleep deprivation has been eyed as a potential treatment for alleviating depression, at least in a proportion of individuals who experience it as a persistent mood.

Sure enough, the researchers behind this latest investigation noticed a lift in the mood in 13 of the 30 patients with major depression following the sleepless night.

Meanwhile, the results of a mood test on those without depression generally reflected the kind of tired crankiness most experience when sleep deprived.

Imaging data revealed a possible explanation behind this contrast. Connections between the amygdala and a bridge between the cognitive and emotional regions of the brain called the anterior cingulate cortex seemed to be enhanced in those whose moods reportedly improved, regardless of their mental health.

Even after two nights of catching up on lost sleep, this connectivity across the two regions remained relatively strong.

Known as chronotherapeutics, the principle of treating psychiatric conditions through changes in biological rhythms has become a field of serious study, suggesting a jolt to our body clock might, in some way, reset regulatory processes that have gone awry.

That's not to say frequent sleepless nights are necessarily a good idea for anybody, with sleep disturbance linked with higher risks of dementia later in life. Messing with the body's clock can come at a cost to our health, our social life, and our working day.

Mapping dramatic changes in communication between areas of the brain known to be involved in emotional and cognitive regulation following a loss of sleep could go some way to establishing possible mechanisms responsible for at least some cases of depression, however.

The World Health Organization ranks major depressive disorder as the third greatest disease burden around the globe. Knowing it's at least possible to enhance the connectivity between areas of the brain critical to mood, we might one day find a way to lift the moods of millions without robbing our brains of the benefits of a good night's rest.

This research was published in PNAS.