We might have a brand new type of contraceptive on our hands, with scientists inventing sticky beads that can mimic female eggs in the uterus, and act as decoys to lure in sperm, bind to them, and block them from reaching the real thing.

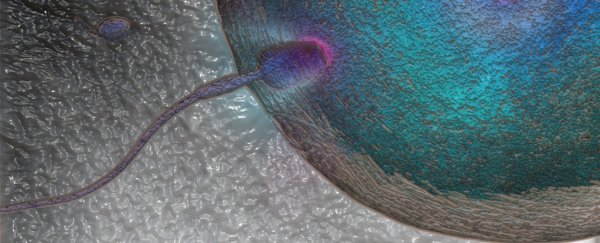

The beads, which have so far only been tested in mice, do their thing thanks to a protein called ZP2, which exists on the zona pellucida – the surface of mammalian eggs. During conception, a sperm cell recognises a molecular fragment of ZP2 and binds to it, enabling the egg to be penetrated and fertilised. By mimicking this process with inert beads coated in the same protein, the sticky beads are effectively a honey pot to trap unwitting sperm.

In the study, a team from the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases embedded the sticky beads into the uterus of female mice.

When the treated female mice mated with males, the technique successfully blocked the sperm's passage within the reproductive tract. All of the treated females avoided pregnancy during continuous mating in the experiment, whereas the untreated females fell pregnant as per normal.

This effect lasted for several weeks but was not permanent, with the treated mice eventually regaining fertility. This suggests that the sticky beads could offer a long-term but ultimately reversible contraceptive.

Of course, there'd need to be an awful lot more testing done to make sure the beads were safe and effective for humans to use before you can expect to see these on the shelf in your local pharmacy.

And at this point, the researchers acknowledge that there are plenty of other contraceptives out there already. They say the advantage of the ZP2 coating might not be in a new product, but in augmenting other contraceptives to improve their effectiveness.

"You can imagine attaching the peptides to spermicidal sponges, or to vaginal rings impregnated with hormones," one of the team, Jurrien Dean, told James Vincent at The Verge.

But beyond the sticky beads' contraceptive abilities, perhaps the most exciting thing about the research is its potential application for infertility treatments, helping IVF and assisted reproductive technologies (ART) specialists identify superior sperm by seeing how well they bind to the coating.

In the study, the team examined how human sperm bound to the sticky proteins, and they found that sperm that latched on well to the beads also showed an improved ability to bind with mouse zona pellucida.

"Fertility clinics will find the idea of being able to select sperm for use in assisted conception according to their abilities to bind to these beads interesting," reproduction scientist Allan Pacey of the University of Sheffield in the UK, who was not involved in the study, told Sam Wong at New Scientist. "We really do need better methods to do this, as at the moment our abilities to select the best sperm is somewhat arbitrary."

The results have been reported in Science Translational Medicine.