Neolithic farmers living in Italy around 7,000 years ago had an unusual ritual to help their dead make passage beyond the world of the living - removing their skin and muscle, and hiding their bones.

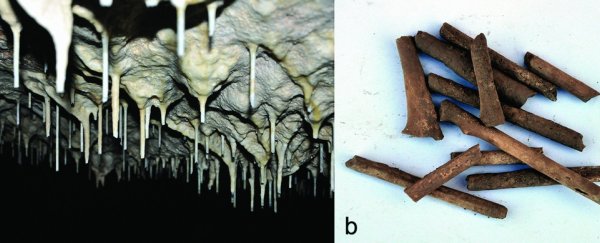

It likely began ordinarily enough: with the burial of the dead on the outskirts of a settlement. But after about a year, the corpses were dug up and the flesh was scraped from their bones. These 'clean' remains were then scattered inside a giant stalactite-filled cave, along with animal bones, stone tools, and pottery.

"[Defleshing] is something which occurs in burial rites around the world but hasn't been known for prehistoric Europe yet," archaeologist John Robb from the University of Cambridge in the UK told Garry Shaw from Science Magazine.

This provides the "first well-documented case for early farmers in Europe of people trying to actively deflesh the dead," Robb added.

Robb and his team examined more than 2,800 identifiable bone fragments from at least 22 Neolithic humans who died around 7,500 years ago.

These bones were uncovered from Scaloria Cave in the Tavoliere region of southeastern Italy. As the cave had been sealed off from contact until its discovery in the 1930s, the remains were well-preserved.

The first thorough excavation occurred in 1979, the findings of which "are only now reaching full publication" the researchers say, and are revealing new insight into the post-mortem handling of these human bones.

In their study, which has been published in the journal Antiquity, the researchers show that in this ancient Italian community, select bones were defleshed, rather than whole skeletons.

And as Shaw explains for Science Magazine, their observation of light cut marks also suggests "that only residual muscle tissue needed to be removed by the time of defleshing. That meant the remains were likely deposited as much as a year after death."

Light cuts on a fibula shaft (Credit: John Robb)

Light cuts on a fibula shaft (Credit: John Robb)

With this in mind, the research team suggests that the defleshing was only one part of a long and multi-stage burial process. As the bones don't appear to have any damage from scavenging animals or weather, it's likely they were initially stored or buried deep in the ground. After about a year, select bones were removed, defleshed, and placed inside the cave with personal items, such as tools.

"People in our culture tend to shun death and try to have brief, once-and-for-all interactions with the dead," Robb told Science Magazine. "But in many ancient cultures, people had prolonged interaction with the dead, either from long, multistage burial rituals such as this one, or because the dead remained present as ancestors, powerful relics, spirits, or potent memories."

The researchers think the cave itself might also hold some special significance to the ceremony, as defleshed bones have similar appearances to stalactites. Neolithic humans collected dripping water from these rock structures.

"It's thus possible, the team says, that the cleaning process and deposition in the cave was a way for the living to return the bones to their stone-like origins, both in appearance and location, completing a cycle of incarnation,"writes Shaw.

"It may be that they regarded life as originating from forces or substances underground," Martin Smith, a biological anthropologist at Bournemouth University in the UK, who was not involved in the research, told Science Magazine. "Or they may have believed subterranean places to be where the soul traveled to after death. Either way, it gives a level of insight into Neolithic beliefs that we wouldn't normally have access to."

We love unusual burial rituals. In Poland about 400 years ago, people believed to be vampires were buried with heavy stones on their necks, presumably to prevent them from rising from the grave. Meanwhile, in the catacombs below Italy's Capuchin Monastery, thousands of mummies can be found in their best threads, and no one really knows why.

Source: Science Magazine