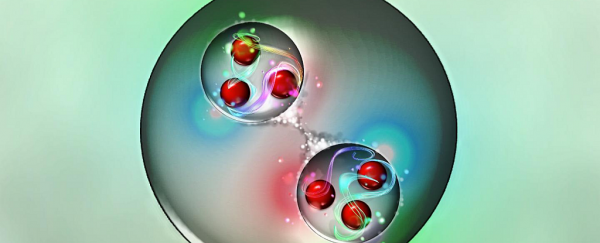

Using one of the most powerful computers in the world to perform complex simulations, scientists have predicted a new type of dibaryon particle - one that has two baryons instead of the usual one, with quarks all of the same colour.

The researchers, from the Japanese HAL QCD Collaboration, are calling the particle di-Omega.

Baryons are particles that contain three quarks, the subatomic particles that are one of the fundamental constituents that make up matter, and they make up most of the normal matter in the Universe. Protons and neutrons - which make up atomic nuclei - are baryons.

The charge of baryons is dependent on the "colours," or types, of the quarks inside, of which there are six - up, down, top, bottom, charm, and strange.

In nature, there is only one known particle that's made up of two baryons, or a dibaryon particle (also known as a hexaquark). It's called deuteron, and it consists of a proton and a neutron bound together to form the nucleus of deuterium, or heavy hydrogen.

Although scientists believe that other dibaryons might exist, so far none have been conclusively found.

But by running simulations based on quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the theory that describes quark interactions, the HAL-QCD Collaboration is able to model potential stable dibaryons.

But it's not easy - the more quarks there are in the mix, the more complex their interactions, which means more computing power is needed.

That's why the researchers employed the K Computer at RIKEN's Advanced Institute for Computational Science, which has a computational power of 10 petaflops, or 10 quadrillion operations per second.

Even so, it took almost three years to reach a conclusion on the particle. But reach a conclusion it did.

Di-Omega consists of two Omega baryons, containing three strange quarks each. It is, the researchers said, the "most strange" of all the potential dibaryons.

The research builds on the collaboration's previous work - in 2011, they announced the discovery of a theoretical dibaryon with two up, two down and two strange quarks. But since then they have refined their methods, devising a new theoretical framework, and a new algorithm, to allow for more efficient calculations.

And, of course, the access to the K Computer, which became available for use by researchers in 2012, made an enormous difference.

Going forward, the researchers believe their work can be applied to experimental settings to search for evidence of these particles in the real world.

"We believe that these special particles could be generated by the experiments using heavy ion collisions that are planned in Europe and in Japan," said quantum physicist Tetsuo Hatsuda of RIKEN.

"We look forward to working with colleagues there to experimentally discover the first dibaryon system outside of deuteron."

The team's work has been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.