The water distribution inside the Moon appears to be somewhat lopsided.

According to an analysis of lunar materials collected from the far side of the Moon and delivered into the waiting hands of scientists, our natural satellite has less water on the side that permanently faces away from Earth.

This information is pretty interesting. The surfaces of the two hemispheres of the Moon are markedly different from each other. The far side is heavily crater-scarred; the near side is punctuated with large, flat, basaltic maria, or plains, created by widespread volcanic activity long ago.

This difference is a strange puzzle. A hemispherical difference in the interior composition of the Moon could help explain its piebald exterior.

"Water abundance in the lunar mantle provides insights into the giant impact formation models for the Moon and plays a crucial role in the crystallization of the lunar magma ocean and subsequent magmatism and long-lived volcanism," writes a team led by planetary physicists Huicun He and Linxi Li of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

"The new estimate for the lunar farside mantle represents a landmark for estimating the water abundance of the bulk silicate Moon, providing critical constraints on the giant impact origin hypothesis and the subsequent evolution of the Moon for which the role of water is central."

The current best model for the formation of the Moon starts with a giant collision sometime more than 4.5 billion years ago. A planetesimal around the size of Mars named 'Theia' smacked into a baby Earth during the Solar System's earliest epoch, sending debris flying that coalesced in Earth orbit to form the Moon.

For a while, the Moon was squishy on the inside. It oozed out a huge volume of magma on the side nearest Earth to form the lunar maria, a process that took place between around 3.9 and 3.1 billion years ago. The relative absence of maria on the Moon's far side is a striking contrast.

We've got some ideas about why this may be. The crust on the facing hemisphere is thinner, a trait associated with uneven cooling as heat from Earth kept the near side warmer as the two bodies cooled from the heat of formation.

There could be more to it, and when China's Chang'e-6 mission became the first to bring samples of the far side of the Moon to Earth, humanity finally had the material it needed to study the Moon's patchy chemical composition.

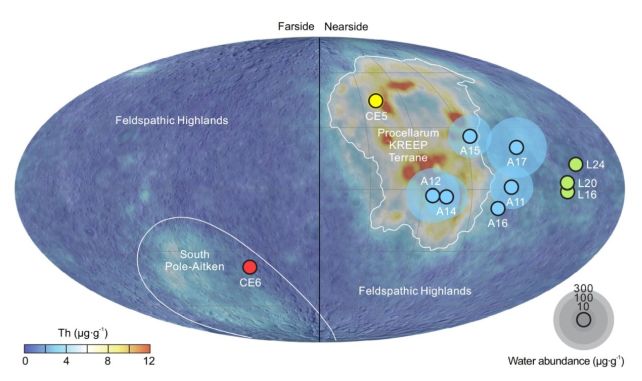

Previous studies have shown that the distribution of water in the interior of the Moon is quite heterogenous, varying from 1 to 200 micrograms per gram, mostly derived from materials collected from the Procellarum KREEP Terrane on the lunar nearside, a region rich in potassium, phosphorus, and rare-earth minerals.

Previous analysis has proposed that the giant impact formation mechanism may have resulted in the observed asymmetries on the Moon. One possible marker for this is chemical abundances, with less water expected on the far side.

There isn't a lot of basalt on the far side to compare to near-side basalts, but the giant South Pole-Aitken Basin on the lunar far side from which Chang'e-6 collected its minerals is one exception.

He, Li, and their colleagues performed scanning electron microscopy and electron probe microanalysis of a sample of the Chang'e-6 material. In particular, they looked for signs of hydration in minerals such as olivine and ilmenite trapped inside the basalt.

Their results showed that the source of the magma that produced the South Pole-Aitken Basin basalt didn't have much water in it at all – around just 1 to 1.5 micrograms per gram of rock.

Now, it's possible that there's another reason for this relative dryness compared to the near side. The basin covers a quarter of the Moon's surface; the impact that produced it would have been pretty shocking. Maybe, the scientists propose, the impact pushed a bunch of material over towards the near side.

It's also possible that other parts of the far side interior are a bit wetter; after all, this is just one sample.

But, so far at least, the findings are consistent with the evidence we'd expect to find for a giant impact formation.

Now we just need to nip up there and grab a few more handfuls of Moon dirt. For science.

The research has been published in Nature.