Just over a year ago, at the end of February 2019, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) pulled off an amazing feat. It brought the Hayabusa2 probe down to the surface of asteroid Ryugu for a sample collection, then bounced it back up into orbit.

As Hayabusa2 lifted back off again, its cameras snapped something peculiar - the probe's thrusters had left dark smudges on the asteroid's surface. Now those weird smudges have helped astronomers solve the mystery of the asteroid's peculiar colouration.

"Two distinct types of material are present on the surface with different colours: bluer material distributed at the equatorial ridge and in the polar regions and redder material in the mid-latitude regions. However, the cause of these spectral variations is not understood," the researchers wrote in their paper.

(JAXA, University of Tokyo & collaborators)

(JAXA, University of Tokyo & collaborators)

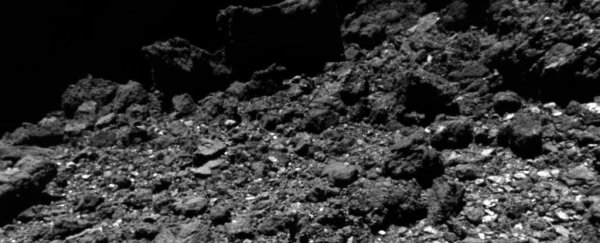

As Hayabusa2 touched down on Ryugu on 21 February 2019, it also managed to take high-resolution images of the surface, with details resolved at up to 1 millimetre per pixel.

"Those images allow us to observe the surface's response to the physical disturbances generated by the touchdown, including the sampling projectile collision and the firing of the spacecraft's thruster gas jets," the team wrote.

Images and observations of the asteroid had already determined that the asteroid was mottled like a tortoiseshell cat, and the sampling site was partially chosen because it provided a mixture of both the red and the blue kinds of material.

But when Hayabusa2 launched back into orbit, the layer of material it disturbed seemed to correspond with the redder material, rather than the blue stuff.

As they studied the asteroid, the researchers also noticed a few peculiarities about the distribution of the two materials. Larger boulders tended towards blue, while the more fine-grained material around them - dirt and rubble - tended towards red. Craters filled with bluer material were found to be younger than red-filled craters, as though the impact had knocked through the red top layer and exposed the blue surface underneath.

All this suggested that the asteroid's rock was originally on the blue side, and had become reddened by some process.

It also suggested that the process that reddened the rubble had occurred on a longer timeframe than it takes for boulders to become exposed through processes such as impact disruption or thermal fatigue.

Luckily, we know of processes that can and do redden asteroids on a pretty regular basis: space weathering and solar radiation. This can occur over a long period of time, but space weathering typically only reddens a very thin surface layer of a few nanometres, compared to solar radiation. And it seems Ryugu's red layer was initially a few tens of centimetres.

(Morota et al., Science, 2020)

(Morota et al., Science, 2020)

"We suggest that a surface reddening event within a short period of time could be explained if Ryugu underwent a temporary orbital excursion near the Sun, causing higher surface heating," the researchers wrote in their paper.

But the scientists were able to figure out timeframes for when this might have occurred, too. Ryugu's surface suggests the asteroid is very young, only about 9 million years old. It started its life in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, where collisions with other bodies are much more frequent than they are in the near-Earth orbit the asteroid later entered.

Most of the large craters on the asteroid are red. This suggests that Ryugu gained its red hues after it left the asteroid belt, where it experienced more frequent collisions.

A model that estimates the frequency of these collisions over time allows us to put a timeframe on when the reddening occurred. If the reddening occurred after the asteroid left the main belt, it probably occurred around 8 million years ago, based on the number of large blue craters.

If Ryugu stayed in the belt, the reddening could have occurred as late as 300,000 years ago.

There are ways astronomers can try to narrow it down. They can try to simulate Ryugu's orbit back through time to see when it might have been close to the Sun. But the samples Hayabusa2 collected during its touchdowns are expected to be very revealing.

"The large local variations in the spectral slope and albedo within the sampling site on Ryugu suggest that both bluer and redder components were likely collected during the touchdown of Hayabusa2," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"We predict that the returned sample will contain a mix of altered and unaltered materials, with the former recording a solar heating event."

The research has been published in Science.