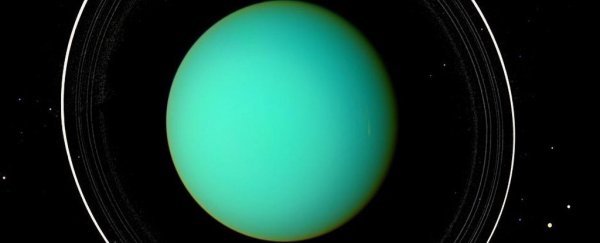

Saturn may be the most showy, but it's not the only planet in the Solar System circled by rings. And last year we found out more about the 13 rings around Uranus when it photobombed a thermal image astronomers took of the ice planet.

For the first time, researchers were able to determine the temperature of the rings, and confirmed that the main ring - called the epsilon ring - is like none other in the Solar System.

Usually, Saturn is the only one pictured with rings, because the ones circling Uranus, Jupiter, and Neptune can only be seen with powerful telescopes (or probes such as Juno, which snapped this breathtaking photo of one of the ghostly Jovian rings).

How many rings could there be? Jupiter has four. Neptune has five. Saturn has thousands.

When it comes to Uranus, we don't know much about its rings, since they reflect very little light in the optical and near infrared wavelengths typically uses for Solar System observations. In fact, they're so dim, they weren't even discovered until 1977. (Jupiter's were discovered in 1979, and Neptune's in 1984.)

(Edward Molter and Imke de Pater/UC Berkeley)

(Edward Molter and Imke de Pater/UC Berkeley)

So it was somewhat unexpected when the rings showed up in thermal images astronomers took to explore the temperature structure of the planet's atmosphere; particularly clear was the epsilon ring.

"We were astonished to see the rings jump out clearly when we reduced the data for the first time," said astronomer Leigh Fletcher from the University of Leicester.

Because it was a thermal image, for the first time the team could learn the temperature of the rings: just 77 Kelvin, the boiling point of liquid nitrogen at standard atmospheric pressure. (The surface temperature of Uranus gets as low as 47 Kelvin, so it's even cooler.)

It also confirmed that the rings are really weird, when compared to those around other planets. See, when Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in 1986 and took a bunch of happy snaps, scientists back home noticed that the rings seemed to be missing something.

In Saturn's rings, the particles run the full size gamut, from powdery dust to chunky boulders. Jupiter and Neptune both have very dusty rings, composed mostly of fine particles.

Meanwhile, Uranus has sheets of dust between its rings, but the rings themselves only contain chunks upwards the size of a golf ball.

"We don't see the smaller stuff," said astronomer Edward Molter of UC Berkeley.

"Something has been sweeping the smaller stuff out, or it's all glomming together. We just don't know. This is a step toward understanding their composition and whether all of the rings came from the same source material, or are different for each ring."

(Molter et al., arXiv, 2019)

(Molter et al., arXiv, 2019)

Possible sources include impact ejecta from moons, like seen in Jupiter's rings; asteroids captured by the planet's gravity, then somehow pulverised; debris left over from the planet's formation (not likely, since they're thought to be around 600 million years old at most); or debris from the theorised impact that literally knocked the planet sideways.

The most likely explanation is solid orbiting objects, destroyed either by impacts or tidal forces.

And that's not all. According to previous data, including images in near-infrared taken using the Keck Observatory in 2004, the very composition of the rings around Uranus is different from others.

"The albedo is much lower: they are really dark, like charcoal," Molter said. "They are also extremely narrow compared to the rings of Saturn. The widest, the epsilon ring, varies from 20 to 100 kilometres wide, whereas Saturn's are hundreds or tens of thousands of kilometres wide."

So, even with the stunning new pics, the rings are still a huge mystery. But a mystery that may have more clues soon, when the James Webb Space Telescope, with its state-of-the-art observation tech, hits the sky in 2021. We hope looking at Uranus warrants some of its valuable time.

Meanwhile, the research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.

A version of this article was originally published in June 2019.