A new portrait from the world's most powerful solar telescope has captured the face of our Sun in exquisite detail.

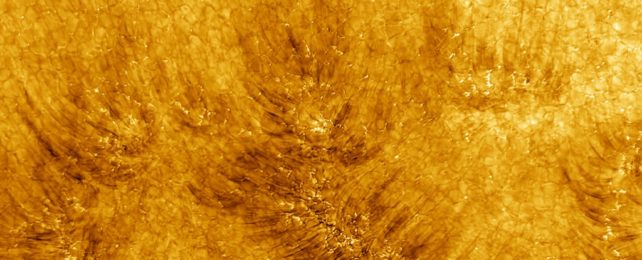

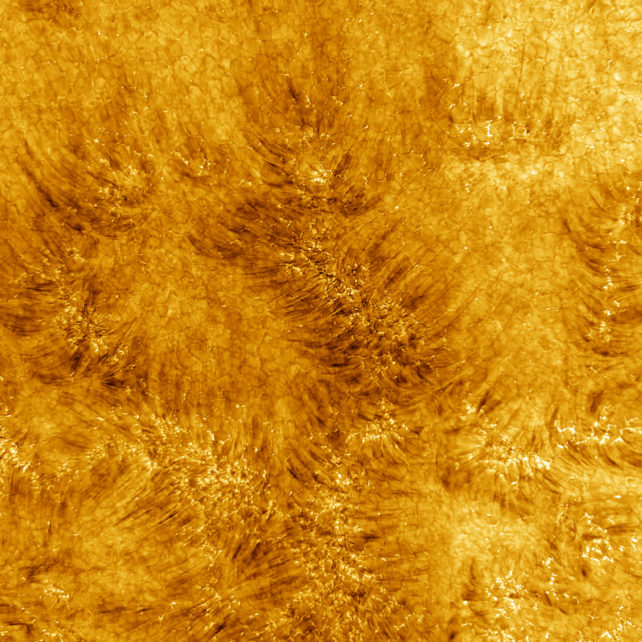

Up close and personal to the giant star, at a resolution of just 18 kilometers, the middle layer of the Sun's atmosphere, known as the chromosphere, looks almost like a shag rug.

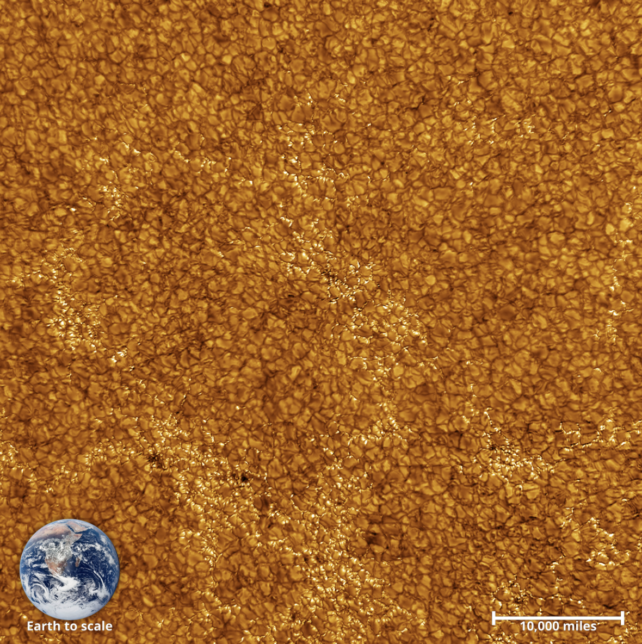

Bright hairs of fiery plasma can be seen in the image above, flowing into the corona from a sort of honeycomb-like pattern of pores, more easily visualized in the image below. These blistering blobs are known as granules, and each is about 1,600 kilometers (994 miles) wide.

Each of these portraits is about 82,500 kilometers (51,260 miles) wide, which is only a single-digit percentage of the Sun's total diameter.

To put the sheer enormity of these images into context, astronomers have placed our own planet over the top for scale.

The mind-boggling achievement marks the one-year anniversary of the Inouye Solar Telescope – the most powerful instrument of its kind – and the culmination of 25 years of careful planning.

The Sun's chromosphere, which sits below the corona, is usually invisible and can only be seen during a total solar eclipse, when it creates a red rim around the blacked out star. But new technology has changed that.

Never before have we gazed this closely into our Solar System's light source. The Inouye telescope is able to see features within the Sun's chromosphere as small as the island of Manhattan.

Last year, when the nearly-finished telescope released its first images, solar physicist Jeff Kunh called it "the greatest leap in humanity's ability to study the Sun" since the time of Galileo.

Now, astronomer and space telescope scientist Matt Mountain, president of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), says we have cut the ribbon on a "new era of Solar Physics".

The insights gained from this new perspective will help scientists predict and prepare for solar storms, which can send a tsunami of hot plasma and magnetism all the way from the Sun's corona to Earth, possibly causing global blackouts and internet outages for months.

"In particular we thank the people of Hawai'i for the privilege of operating from this remarkable site, to the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the US Congress for their consistent support, and to our Inouye Solar Telescope Team, many of whom have tirelessly devoted over a decade to this transformational project," Mountain said in a recent announcement.

The Inouye Solar Telescope is built on the Maui volcano, Haleakalā, which is culturally and spiritually important to Native Hawaiian people. The NSF proudly claims to have included native Hawaiian input throughout the telescope's construction, and yet some native people say the instrument still feels like an affront by white colonizers.

Another massive telescope destined for the dormant volcano, Maunakea, has met much resistance from native Hawaiians, who do not want their sacred site desecrated for the purposes of western science.

It's clear that the Inouye Solar Telescope is a massive scientific achievement for modern astronomers, yet it comes at a cultural cost to an ancient community of stargazers.

Long before Galileo, native people around the world were using the Sun, the Moon and the stars to better understand our place in the Universe.

The Inouye Solar Telescope allows us a glimpse at the center of our Solar System like never before, but as our focus narrows, we must not lose sight of stargazers who came before.

Standing on their shoulders gets us closer to the stars.