For eons, humans have worn personal ornaments that tether them to their people; precious items that reflect a clan identity through life and into the grave. But those cultural associations don't always follow family lines.

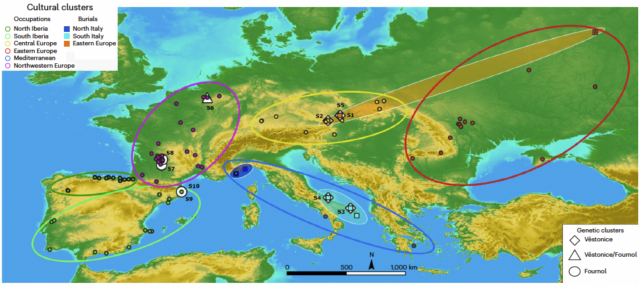

A new study comparing thousands of pendants from across ice age Europe, dating to between 34,000 and 24,000 years ago, suggests there were at least nine distinct cultural groups of hunter-gatherers within the broader population referred to as the Gravettians, each with their own relatively distinct styles of ornament.

Additional analyses of genetic data from burial sites reveal that some of these categories shared the same cultural embellishments even though they were of different ancestries.

"We've shown that you can have two [distinct] genetic groups of people who actually share a culture," Jack Baker, lead author of the study and archeology doctoral student at the University of Bordeaux in France, told Scientific American's Sarah Wild.

The earliest known instance of ancient humans adorning themselves with beads dates back to around 140,000 years ago, with shell beads found in modern-day Morocco. But the practice of wearing beads really exploded about 45,000 years ago, when ornamental traditions spread across Europe.

"This is the moment when personal ornaments acquire a degree of diversity, enabling researchers to more precisely investigate their role as cultural markers," Baker and colleagues explain in their paper.

To investigate, Baker compiled existing records of thousands of hand-chiseled beads and pendants found at 112 sites dotted across Europe, from Portugal to Russia.

Based on their age and other associated artifacts, these ornaments had previously been lumped together as one culture, the Gravettian people. Best known for their venus figures, including the Venus of Willendorf, this widespread population thrived across Europe for around 10,000 years before dying out before the peak of the last ice age.

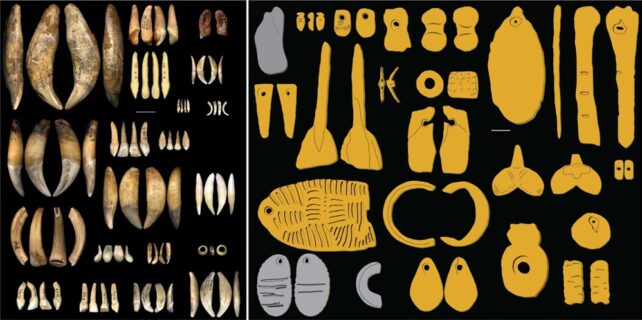

But the diversity of ornaments, once collated en masse, was striking. The researchers identified 134 different types of beads that the Gravettians had crafted from animal bones, teeth, shells, amber, and stone. Some resembled fishtails; others owls.

While most of the trinkets were found in the ruins of Gravettian dwellings, some were excavated from burial sites where DNA samples had also been collected.

Comparing ornaments across geographical distances, Baker and colleagues identified nine distinct cultural groups with unique preferences for different types of beads depending on their geography.

Baker says these differences had 'crystalized' in the artifacts found in graves, and could have been worn as a way for people to quickly identify each other.

However, the analysis also suggests that cultural boundaries were at times fluid, with neighboring groups occasionally swapping styles.

Moreover, when the patterns among artifacts were layered over genetic evidence, a more complex story emerged.

The researchers identified two distinct cultural groups in modern-day Italy where DNA evidence had suggested only one existed. And, in another region, spanning present-day France and Belgium, individuals of different genetic backgrounds decorated themselves with the same types of cultural keepsakes.

Researchers have previously cautioned against muddling archeological and genetic evidence. However, archeologist Peter Jordan from Lund University and Hokkaido University has lauded Baker and colleagues' paper as a "landmark study" that reveals how examining ancient artifacts and DNA in tandem can reveal rich tapestries of cultural behaviors and group relations that aren't detectable by studying either DNA or artifacts alone.

The findings also strike a chord that even during bleak ice ages, our ancestors whittled and carved beautiful pendants to identify their people and distinguish themselves from others, Baker says.

"The sense of belonging felt by all humans today is deeply rooted in our shared history and played an important role in determining how Gravettian people adorned themselves," the team concludes.

The study has been published in Nature Human Behaviour.