In the past it was difficult for scientists, let alone the public, to get a full picture of each animal's inner workings, but with rapid advances in 3D scanning technology, even school children can now digitally 'dissect' these precious specimens.

That's the goal of openVertebrate (oVert), a project involving 18 institutions that has spent the past five years creating 3D reconstructions of museum specimens, which are now available freely online.

The animals on display behind glass at the museum are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to museum collections, which contain thousands of specimens that have been collected and carefully preserved over the decades.

But the physical limits to accessing these specimens have always hindered scientific collaboration and education.

"If you require someone to get on a plane and travel to you to collaborate, that's prohibitive in a lot of ways," says herpetology curator from the Florida Museum of Natural History David Blackburn, who led the oVert project. "Now we have scientists, teachers, students and artists around the world using these data remotely."

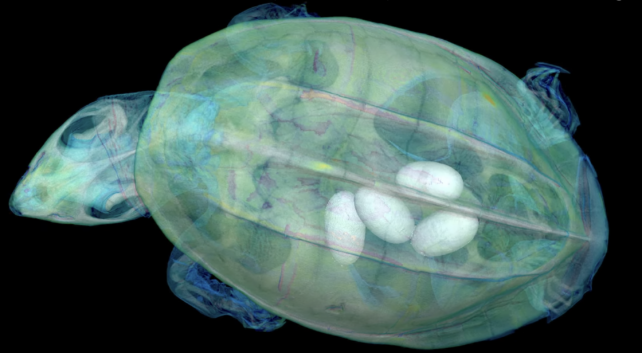

A pair of tortoises from the California Academy of Sciences are among the many vertebrates now in the digital collection.

"They have the largest Galapagos tortoise collection in the world. These are not things you put in boxes and loan," Blackburn says.

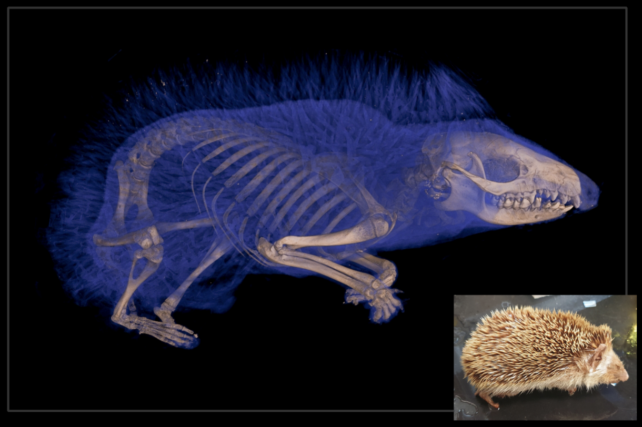

Already, the process of scanning specimens has given scientists new perspectives on subjects they've been studying for years.

While scanning spiny mice for the project, Florida Museum of Natural History's digital imaging director Edward Stanley noticed their tails were covered in internal bony plates called osteoderms, previously thought to be unique to armadillos.

"All kinds of things jump out at you when you're scanning," Stanley says.

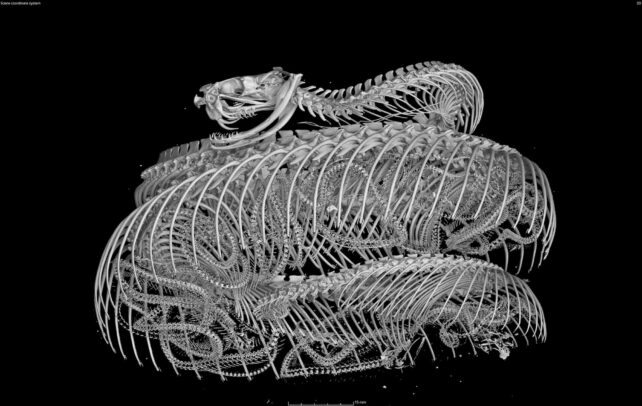

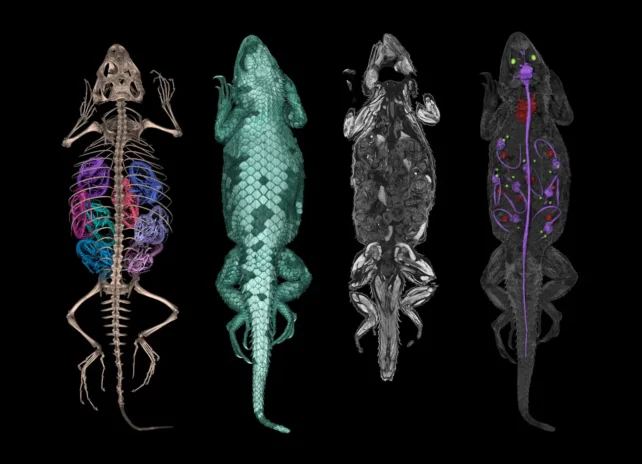

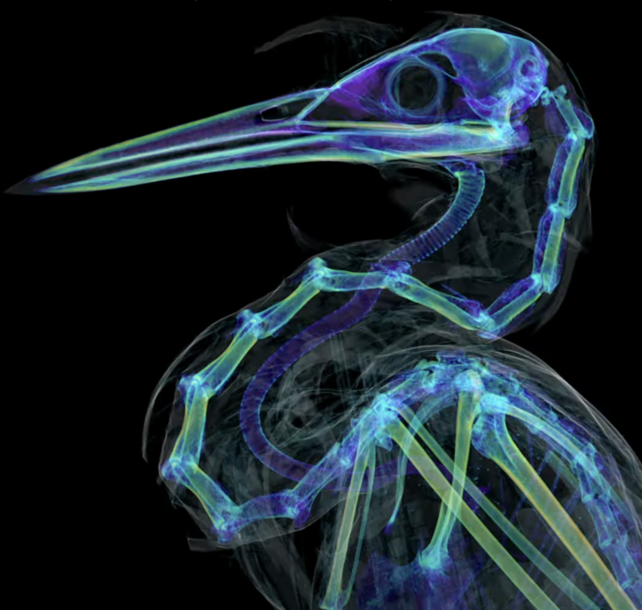

The scans allow us to see into the specimens in a way that was previously only possible through destructive dissection and tissue sampling, offering views of the skeletons and, in some cases, the soft tissues that are hidden within a specimen's interior.

"Museums are constantly engaged in a balancing act," Blackburn says. "You want to protect specimens, but you also want to have people use them. oVert is a way of reducing the wear and tear on samples while also increasing access, and it's the next logical step in the mission of museum collections."

Already, they've revealed the cause of death of a rim rock crowned snake (Tantilla oolitica); that Spinosaurus would have been a terrible swimmer; and that frogs have lost teeth at least 22 times in their evolutionary history, sometimes re-evolving them later.

The project has always had school kids in mind as potential end-users for these models, and have already trained some teachers in using them in the classroom.

"It's been a game-changer for my evolution unit," says Jennifer Broo, a high school teacher in Cincinnati.

"I teach juniors and seniors, and I absolutely love them, but they can be a tough audience. They know when things are fake, which makes them less engaged. Using the oVert models, you can teach concepts at an appropriate level while also maintaining the authenticity of the science."

With more than 13,000 specimens scanned, where to start? Well, it's all still a bit difficult to navigate, but these color-coded 3D anatomy diagrams from Blackburn's lab at the University of Florida are worth exploring.

Or what about an incredible cave angelfish animation from the Florida Museum?

Better yet, why not try an interactive wheel showing the diverse structures of bird wing bones?

You can visit Sketchfab anytime for a user-friendly sample of the 3D interactive models. The full repository of 3D scans is available on MorphoSource.

A paper summarizing the project was published in BioScience.