The climate crisis is affecting our planet to such an extent, summers in the Northern Hemisphere could last half the year by 2100, scientists have warned.

This doesn't mean longer days lounging in the sunshine, but dramatic impacts on human health, agriculture, and ecology.

While an extended period of balmy weather might initially sound appealing, such a significant shift in the seasons has the potential to cause huge disruption to ecosystems that are often finely balanced in terms of timings and temperatures.

From extended heatwaves and wildfires, to changing migration patterns affecting the food chain, the study concludes that if global warming continues at the current rate, the risks to humanity are only going to get more severe over time – and the changes are already happening.

Recorded and predicted shifts in Northern Hemisphere seasons. (Wang et al. 2020, Geophysical Research Letters, AGU)

Recorded and predicted shifts in Northern Hemisphere seasons. (Wang et al. 2020, Geophysical Research Letters, AGU)

"Summers are getting longer and hotter while winters shorter and warmer due to global warming," says physical oceanographer Yuping Guan, from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. "More often, I read some unseasonable weather reports, for example, false spring, or May snow, and the like."

The researchers looked at historical daily climate data from 1952 to 2011, marking the days with the hottest 25 percent of temperatures over those years as the summer months, and those with the coldest temperatures as the winter months.

The analysis revealed summer grew on average from 78 days to 95 days from 1952 to 2011, and winter shrank from 76 days to 73 days. Spring and autumn shrank too, by 9 days and 5 days respectively. While spring and summer have gradually been starting earlier, autumn and winter have been starting later.

Next the team turned to future climate models to predict how these trends might continue until the turn of the century, finding that the Northern Hemisphere could have a summer that starts in early May and ends in mid-October by 2100.

That's a potentially dangerous development for all kinds of reasons – it would mean more time with allergenic pollen in the air, for example, and the further spread of disease-carrying tropical mosquitoes, to name just two consequences.

"Numerous studies have already shown that the changing seasons cause significant environmental and health risks," says Guan.

Based on the data collected since 1952, the Mediterranean region and the Tibetan Plateau have seen the most change when it comes to seasonal cycles, but it's unlikely that any part of the globe is going to be able to escape the knock-on effects of climate change.

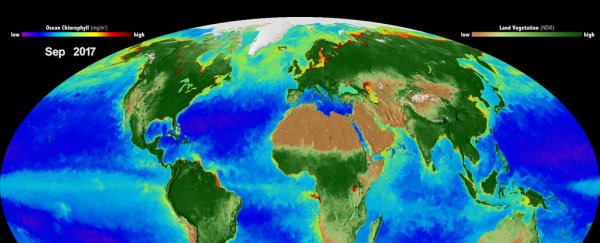

As temperatures shift ever-upward, we're seeing the weather patterns of the world change beyond the point of no return – and every weather variation has an impact on the oceans and the land underneath.

If we're going to be able to pull back from the brink of a planet that heats up beyond our control, it's important to gather as much data as possible to inform the sort of tough decisions that are going to be needed.

"This is a good overarching starting point for understanding the implications of seasonal change," says climate scientist Scott Sheridan, from Kent State University, who was not involved in the study.

The research has been published in Geophysical Research Letters.