Continent-sized structures of mineral protruding from the lower mantle towards Earth's outer core may be contributing to an instability of our planet's magnetic field.

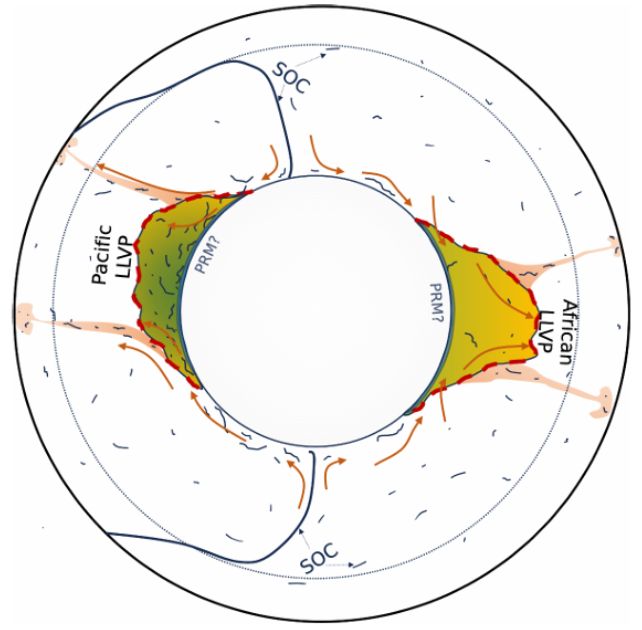

The two odd formations – one under the Pacific and the other beneath Africa – resemble each other in terms of seismic waves, so were assumed to have the same composition.

Cardiff University geodynamicist James Panton and colleagues have now concluded otherwise, determining the two regions are made of different materials and have different histories. If true, it could affect heat flow and convection deep within our planet in ways that could influence the way Earth generates its magnetosphere.

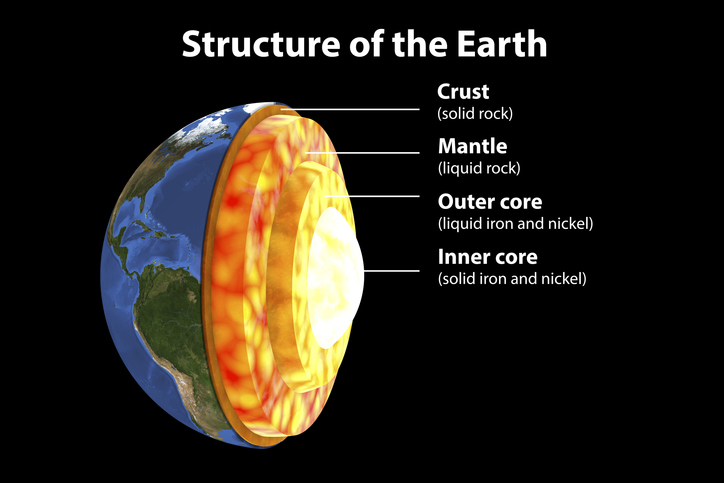

Up to 900 kilometers (560 miles) high and thousands of kilometers wide, the two "large low-velocity provinces" have puzzled scientists since they were revealed by seismic data in the 1980s. Research has since suggested they're at least, in part, composed of former oceanic crust.

"It is … fascinating to see the links between the movements of plates on the Earth's surface and structures 3000 kilometers deep in our planet," says University of Oxford seismologist Paula Koelemeijer.

Millions of years of natural crust cycling mixed what was once Earth's surface deep into the mantle. The resulting composition now covers up to 30 percent of the core, slowing the seismic waves geologists use to probe Earth's inner structure.

"Our models of mantle circulation over the past billion years demonstrate that large low-velocity provinces can naturally develop as a consequence of recycling oceanic crust," write Panton and team, arguing against competing theories that the anomalies arose from the collision with Earth some 4.5 billion years ago that led to the Moon's formation.

The Pacific structure appears to have 50 percent more fresh oceanic crust mixed through it than the African province, the researchers found. That makes for a greater difference in composition between the Pacific province and the surrounding mantle, not to mention a notable difference in its density.

"We find the Pacific large-low-velocity province to be enriched in subducted oceanic crust, implying that Earth's recent subduction history is driving this difference," says Panton.

The notoriously active Pacific Ring of Fire has consistently replenished the crust material, the team suspects.

In contrast, the region around the African structure is not as geologically active, so the older crust it contains has been more thoroughly mixed in, making this structure less dense.

"The fact that these two large low-velocity provinces differ in composition, but not in temperature is key to the story and explains why they appear to be the same seismically," explains Koelemeijer.

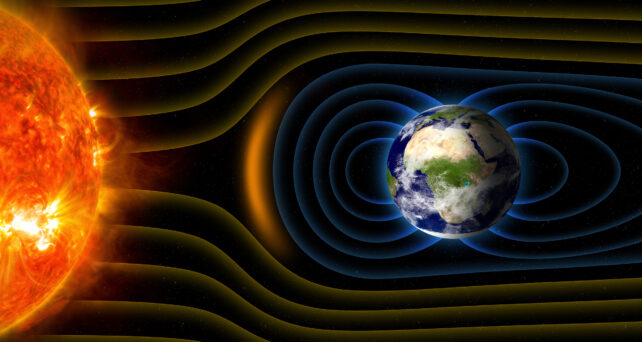

The different temperatures of these two structures, compared to their surrounding regions, impact how heat dissipates from Earth's core, which in turn affects the convection in the core that drives our planet's magnetic field.

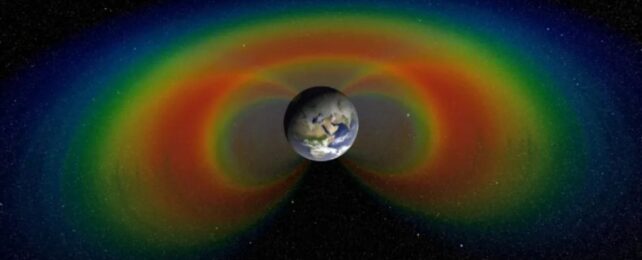

The researchers suspect that as the two mantle structures are not allowing the core's heat to escape evenly on both sides of our planet, they may be contributing to unbalancing the field that maintains our atmosphere's life-supporting qualities.

Africa's large low-velocity province has already been implicated in the weakening of the magnetic field nearby.

The researchers require more data, such as observations from Earth's gravitational field, to better understand the impacts of this deep Earth asymmetry.

This research was published in Scientific Reports.