Climate change is reshaping the evolution and intensity of El Niño events in a way that favors the occurrence of more "super" El Niños, according to a study published Monday.

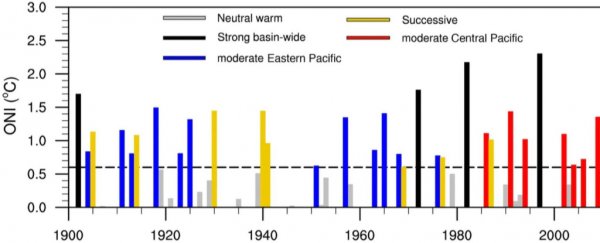

The study examines 33 El Niño events from 1901 through 2017, and concludes that since the late 1970s, there has been a westward shift by up to thousands of miles in where in the Pacific Ocean El Niño is originating and peaking in intensity, as well as a boost in the odds of extremely strong El Niño events.

The westward move is significant, since it means El Niño is now forming and peaking in a region of the Pacific Ocean that is naturally warmer. This can increase the chances of a moderate to strong event.

The multinational team of researchers found that climate change is disproportionately warming the waters of the western tropical Pacific Ocean relative to the Central Pacific. This is influencing trade winds, which tend to blow more strongly from cooler to warmer waters.

The warming trend is also leading to more frequent Central Pacific-based El Niños and for intense El Niño events to first ripple outward from the Western Pacific.

All 11 El Niños that have taken place since 1978 formed in the Central or Western Pacific Ocean, according to the study, including three super El Niños that helped push global temperatures to record levels and wreaked havoc with weather patterns worldwide.

El Niño is a periodic warming of ocean waters along with shifts in trade winds and precipitation patterns in the equatorial tropical Pacific Ocean. By adding tremendous amounts of heat to the ocean's surface and the atmosphere, El Niño events can alter weather patterns worldwide.

This is especially true for the United States during the winter, when California can be pounded by a relentless series of storms.

El Niño's fingerprints can be found from Africa to Asia and even Australia, where it can lead to precipitation extremes.

Super El Niños, like the ones that occurred in 1982, 1998, and 2015-2016, can vault global temperatures to new heights, killing coral reefs worldwide and flooding parts of Africa and Asia while starving other parts of the globe of moisture.

In short, they can lead to lasting extreme weather events affecting hundreds of millions and costing billions of dollars in damage.

How El Niño will change in a warming world has been an elusive but important question for researchers, and there remain many uncertainties. However, the new study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, uses statistical methods as well as eight different computer models to uncover previously unseen trends in El Niño occurrences to date.

The study finds the key may lie in the increasingly mild ocean waters of the western tropical Pacific Ocean — an area known as the West Pacific Warm Pool.

The West Pacific warming, the study's authors propose, is altering trade winds across the equatorial tropical Pacific, triggering El Niño events that propagate from west to east with time.

"I think the main point [of the study] is that El Niño's onset processes has been changed since the 1970s," said lead author Bin Wang, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Hawaii, in an interview.

One difference between the western Pacific El Niños and eastern Pacific events, Wang says, is that the western-based events can begin to affect global weather patterns during the summer in the Northern Hemisphere, rather than reserving the most significant impacts for the winter months.

This can lead to long-lasting drought and heat waves in the Western United States, for example.

The new study comes as scientists are seeking new ways of understanding and predicting climate variability in the tropical Pacific Ocean.

"I think this is a major message … what determines the future change in El Niño intensity is the temperature change in the West Pacific relative to Central Pacific," Wang said.

Study co-author Mark Cane of Columbia University, who is a pioneer in El Niño forecasting, says computer models have failed to accurately simulate changes in the tropical Pacific Ocean during the past few decades.

He says if the West Pacific heats up faster than the East Pacific, it'll cause more El Niño events to be centered toward the international date line, rather than farther east.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.