Black holes are a mystery - dense regions of space where there's so much gravity not even light can escape.

They also have a strange relationship with magnetic fields that's perhaps more mysterious still. We know magnetic fields surround many black holes, but they vary vastly in strength, and we're not really sure how or why they form.

Now thanks to a new study, another piece of this strange puzzle has fallen into place. For the first time, astronomers have observed a magnetic field around a supermassive black hole playing a role in active feeding.

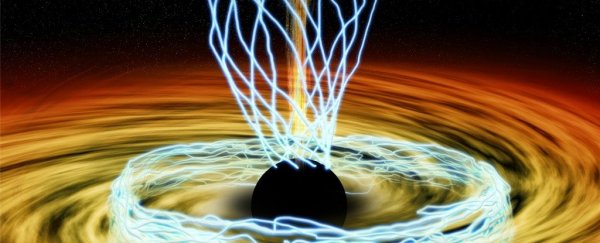

At the heart of Cygnus A - an active galaxy 600 million light-years away and one of the brightest radio sources in the sky - astronomers have seen evidence that magnetic fields are trapping the material that feeds into the supermassive black hole. Sort of like a cosmic net.

This may help scientists figure out why some galactic nuclei are hugely active, spewing out enormous collimated jets from their polar regions, while others - like the Milky Way's own Sagittarius A* - are only intermittently active, and others seem completely dormant.

According to the unified model, active galactic nuclei - that is, a supermassive black hole at the centre of a galaxy that is actively feeding - will be ringed by an accretion disc of material that is falling into the black hole.

Outside that accretion disc is a torus, or doughnut-shaped structure, of dust and gas that feeds into the accretion disc.

How that structure is created, and why it stays there, are unclear - but observations of Cygnus A suggest that magnetic fields are at work to shape the torus and keep it in place.

Illustration showing how magnetic fields would corral the torus. (NASA/SOFIA/Lynette Cook)

Illustration showing how magnetic fields would corral the torus. (NASA/SOFIA/Lynette Cook)

Traditionally, these structures have been difficult to observe in optical and radio wavelengths, but a new instrument is especially sensitive to the infrared emissions from aligned dust grains.

Using the High-resolution Airborne Wideband Camera-plus (HAWC+) on board NASA's Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), astronomers have been able to isolate and observe the dusty torus at the heart of Cygnus A.

"It's always exciting to discover something completely new," said astronomer Enrique Lopez-Rodriguez of the SOFIA Science Center and the Universities Space Research Association.

"These observations from HAWC+ are unique. They show us how infrared polarisation can contribute to the study of galaxies."

It's not entirely clear, either, how black holes' jets form.

We know one thing, they do not originate from beyond the event horizon, from which no electromagnetic radiation can escape.

It is thought that material from the inner edge of the accretion disc travels, again, along magnetic field lines around the outside of the black hole to be blasted out from the poles at speeds approaching that of light.

A recent study, however, found that the black hole called V404 Cygni has a much weaker magnetic field than expected, in spite of its strong jets - which means that the magnetic fields interacting with black holes may not need to be as strong as thought, or some other mechanism is at play.

Either way, future observations will be able to help shed some light on these complex dynamics, and how magnetic fields shape the extreme environments around supermassive black holes.

"If, for example, HAWC+ reveals highly polarised infrared emission from the centers of active galaxies but not from quiescent galaxies," NASA noted, "it would support the idea that magnetic fields regulate black hole feeding and reinforce astronomers' confidence in the unified model of active galaxies."

The team's research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.