The catastrophic Ebola epidemic in West Africa that began in 2013 resulted in almost 29,000 cases of the disease and claimed more than 11,000 lives. Now, scientists say the majority of those cases were caused by a very slim minority of those infected – people called "superspreaders".

According to a new study, these superspreaders amounted to just 3 percent of those infected during the epidemic – but they were ultimately responsible for infecting 61 percent of all cases of the disease.

"In the recent Ebola outbreak, it's now clear that superspreaders were an important component in driving the epidemic," says population biologist Benjamin Dalziel from Oregon State University.

"In our analysis we were able to see a web of transmission that would often track back to a community-based superspreader."

Dalziel and his team analysed data on 200 community burials that took place between October 2014 and March 2015 in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone.

Using computer modelling to reconstruct Ebola transmissions between people who attended these burials, the team found that a small percentage of patients went on to spread the infection to a broad spectrum of others in the community.

"It's similar to looking at a blood spatter pattern and figuring out where the shooter was standing," Dalziel explained to Lena H. Sun at The Washington Post.

"Superspreading was more important in driving the epidemic than we realised."

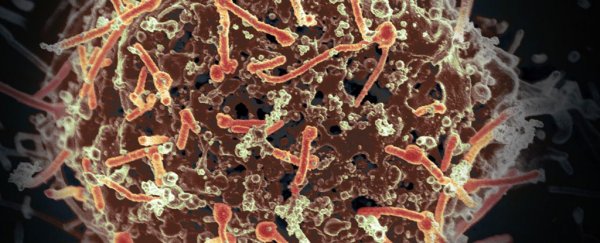

Ebola spreads between humans when people come into contact with the bodily fluids of those infected, such as blood or sweat – or if they touch objects such as clothing or bedding that have been contaminated by these fluids.

As the World Health Organisation (WHO) notes, burial ceremonies where mourners have direct contact with the body of the deceased is one of the key ways Ebola can spread – which is backed up by the latest findings.

According to the Freetown research, on average each infected person passed on the infection to 2.39 other people – with children under 15 and adults over 45 were more likely to be superspreaders.

From the data, it's not possible to put together a profile of specific traits as to why some people infect so many more than others, but the researchers think it's to do with social factors and how those people relate to others in the community.

Young people and older adults are suspected to have come into contact with more people during the epidemic, with greater opportunities to unwittingly pass on infections.

These superspreaders were also more likely to spread the infection within the community – perhaps fearful of the hospital, they stayed at home.

While visiting these infected people at home, it's possible local caregivers in the community may have been more likely to touch or embrace sick children or elderly adults, and in so doing, been infected by them.

Older adults are also more likely to organise and play roles in community burials, which the researchers say is a huge contributor to infections in the Sierra Leone context – and one that can't be separated from the superspreader hypothesis.

"I think that it's events just as much as people. The Sierra Leone case, it really is the event of the funeral," Dalziel told Martha Henriques at International Business Times.

"It's a mixture of the person and the situation."

At funerals and community burials, rituals such as body washing of the deceased can infect a small group of mourners, who then pass it on to potentially hundreds more.

Outside of Africa, the context for transmission would be different – as it would for other types of infections.

Superspreaders have also been identified in previous epidemics, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in 2012.

One SARS patient in Hong Kong saw 20 people infected in a hotel, who then infected 165 more across three countries. During the MERS outbreak, a South Korean traveller infected 29 others, which led to at least another 106 infections.

While each epidemic and context is different, studying how superspreaders pass on their infections within their social environment could help us identify ways to drastically reduce the ultimate number of overall cases during these fatal and devastating outbreaks.

"The overarching idea is of a superspreading context. So targeting those contexts is something that might be possible," Dalziel explains.

"Next time when there's another epidemic, Ebola or otherwise, the evidence suggests it's worth early on asking the question, what are the superspreaders here and what are the important contexts for superspreading happening. It's about targeting interventions to those contexts."

The findings are reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.