The search for life elsewhere in the Universe goes on, but such is the vastness of space, any helpful tips that can point us towards the planets most likely to be habitable are really useful – and scientists think they've just discovered another clue.

A new study outlines what researchers are calling a climate 'decoder', whereby measurements of surface colours and starlight reflections observed on exoplanets could help us figure out the chances of them being able to support life or not.

Working from previous climate and chemistry models, as well as observations of other stars and exoplanets, the methods the astronomers have come up with could help act as a guide to what a distant planet's climate is like.

In other words, the light or spectra that our telescopes see from Earth can effectively be turned into code for the atmospheric conditions of planets outside our Solar System.

"We looked at how different planetary surfaces in the habitable zones of distant solar systems could affect the climate on exoplanets," says planetary scientist Jack Madden from the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University.

"Reflected light on the surface of planets plays a significant role not only on the overall climate, but also on the detectable spectra of Earth-like planets."

Key to these calculations are a planet's albedo, or the amount of light and radiation it reflects back. The team likens it to wearing a black or white t-shirt – one absorbs light and keeps you warmer, while the other reflects it and keeps you cooler.

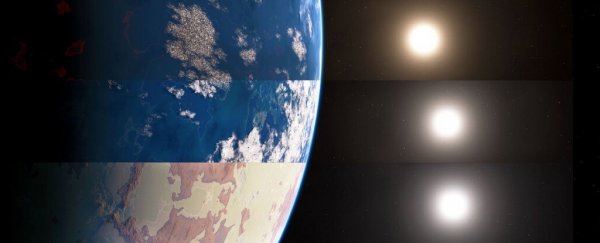

The same is true of planets – their surface, the atmospheric conditions, and the light hitting the planet from its closest star all contribute to its climate, and to how easy it is for life to flourish there.

In the same way that the colour of a t-shirt can tell us how hot its wearer might be getting, the colour of an exoplanet should provide pointers as to just how hot or cold it is on the surface, even though we can't measure that directly.

"Depending on the kind of star and the exoplanet's primary colour – or the reflecting albedo – the planet's colour can mitigate some of the energy given off by the star," says astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger from the Carl Sagan Institute.

"What makes up the surface of an exoplanet, how many clouds surround the planet, and the colour of the sun can change an exoplanet's climate significantly."

The new study builds on previous work from Madden and Kaltenegger, looking at the observable spectra of planets in our Solar System, and what it tells us about their properties, including what they might be made of.

This exoplanet colour 'guidebook' should come in useful very soon: under-construction instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope and the Giant Magellan Telescope will be able to gather atmospheric exoplanet spectra much more easily than we can today – data that researchers will now be able to interpret.

Ultimately, the hope is that we'll be able to focus our attention on the exoplanets that are the most likely to be harbouring life. Whereas previous models have been based on what we know about our own planet and our own Sun, this new approach is better tailored for different types of planets and their host stars.

"Our results show that using a wavelength-dependent surface albedo is critical for modelling potentially habitable rocky exoplanets," the researchers explain in their paper.

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.