It was just about the last thing neurosurgeons in Australia's sleepy bush capital were expecting to find.

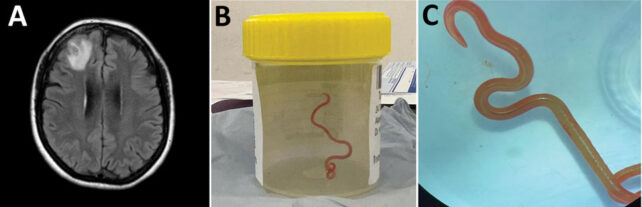

During open-brain surgery on a 64-year-old woman, physicians at Canberra Hospital noticed a long, string-like structure within a lesion affecting her right frontal lobe.

Pulling it out, they realized it was a live, writhing roundworm.

The lead surgeon, Hari Priya Bandi, was left aghast.

"Oh my god, you wouldn't believe what I just found in this lady's brain," Bandi told the hospital's infectious disease specialist Sanjaya Senanayake, according to Melissa Davey at The Guardian.

This is far from the first time parasitic worms have been found wriggling about in a human brain, but this particular nematode was unlike any other cataloged in the medical literature.

Researchers at The Australian National University (ANU) and Canberra Hospital combed through textbooks to figure out where the invader might have came from.

Experts at Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) finally cracked the case.

The parasite surgeons had pulled from this woman's brain was a roundworm called Ophidascaris robertsi, which spends most of its adult life in carpet pythons (Morelia spilota).

"This is the first-ever human case of Ophidascaris to be described in the world," says Senanayake.

Previously, this parasite has been found in juvenile form in the organs of koalas and sugar gliders, but never before in a mammal's brain as a fully-fledged adult.

The worm's life cycle usually starts as a larva in the organs of small mammals, which are then eaten by carpet pythons. The parasite then grows up in the snake's esophagus and stomach.

The patient treated in Canberra has never had direct contact with one of these snakes, but she often forages for native grasses in a lake near her house in southeastern New South Wales.

Researchers suspect a snake in the area shed the parasite's larvae via its faeces. The infection then spread to the woman when she touched or ate the contaminated grass, sometime near the beginning of 2021.

"She initially developed abdominal pain and diarrhea, followed by fever, cough and shortness of breath," says clinical microbiologist Karina Kennedy from Canberra Hospital.

"In retrospect, these symptoms were likely due to migration of roundworm larvae from the bowel and into other organs, such as the liver and the lungs. Respiratory samples and a lung biopsy were performed; however, no parasites were identified in these specimens."

The larvae at this stage were simply too small to be seen. Kennedy says finding one would have been like identifying a needle in a haystack.

Hidden from sight, the larvae matured. By 2022, the patient's symptoms had switched gears. She was experiencing subtle changes in memory, cognitive processing, and depression.

A brain scan revealed a lesion in her right frontal lobe that required surgery. It was here that neurosurgeons found the parasite, sneaking about in full adult form.

Parasitic worms rarely invade the human brain, which is carefully protected from the rest of the body. In this case, the patient was immunosuppressed, which the specialists suspect allowed the worm's larvae to migrate through her blood-brain barrier into the central nervous system.

The fact the larvae could develop into a mature form in a human host is strange and notable, experts say. These worms usually grow up in reptiles, not in mammals.

To ensure that there weren't larvae hiding elsewhere in the patient's body, researchers treated the woman with anti-parasitic drugs.

Her health continues to be carefully monitored.

"It is never easy or desirable to be the first patient in the world for anything," says Senanayake.

"I can't state enough our admiration for this woman who has shown patience and courage through this process."

The case study was published in Emerging Infectious Diseases.