Venus is known for being really quite inhospitable with high surface temperatures, and Mars is known for its rusty red horizons. Even the moons of some of the outer planets have fascinating environments with Europa and Enceladus boasting underground oceans.

Recent observations from the James Webb Space Telescope show that Ariel, a moon of Uranus, is also a strong candidate for a sub surface ocean.

How has this conclusion been reached? Well JWST has detected carbon dioxide ice on the surface on the trailing edge of features trailing away from the orbital direction. The possible cause, an underground ocean!

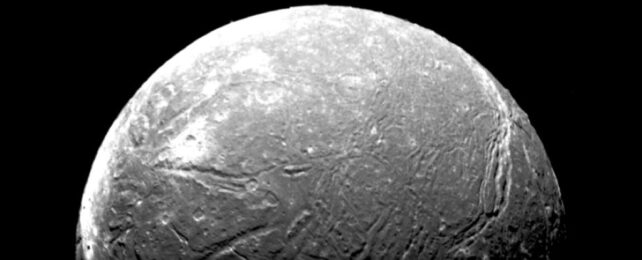

Uranus is the seventh planet in the Solar System and has five moons. Ariel is one of them and is notable for its icy surface and fascinatingly diverse geological features. It was discovered back in 1851 by William Lassell who funded his love of astronomy from his brewing business!

The surface of Ariel is a real mix of canyons, ridges, faults and valleys mostly driven by tectonic activity. Cryovolcanism is a prominent process on the surface, which drives constant resurfacing and has led to Ariel having the brightest surface of all Uranus' moons.

Studying Ariel closeup reveals that the surface is coated with significant amounts of carbon dioxide ice. The trailing hemisphere of Ariel seems to be particularly coated in the ice which has surprised the community.

At the distance of the Uranian system from the Sun, an average of 2.9 billion kilometres, carbon dioxide will usually turn straight into a gas and be lost to space, it's not expected to freeze!

Until recently, the most popular theory that supplies the carbon dioxide to Ariel's surface is interactions between its surface and charged particles in the magnetosphere of Uranus. The process known as radiolysis breaks down molecules through ionisation.

A new study just published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters suggests an intriguing alternative, the carbon dioxide molecules are expelled from Ariel, possibly from a subsurface liquid ocean!

A team of astronomers using JWST have undertaken a spectral analysis of Ariel and compared the results with lab based findings. The results revealed that Ariel has some of the most carbon dioxide rich deposits in the solar system.

The deposits are not just wisps and trace amounts instead adding up to about 10 millimetres across the trailing hemisphere. Furthermore, the results also showed signals from carbon monoxide too, which should not be there given the average temperatures.

It is still possible that radiolysis is responsible for at least some of the deposits but the replenishment from the subsurface ocean is thought to be the main contributor. This hypothesis has been supported by the discovery of signals from carbonate minerals, salts that can only be present due to the interaction between rock and water.

The only way to be absolutely sure is for a future space mission to Uranus. Such a mission will undoubtedly explore the moons of Uranus.

Ariel is covered in canyons, fissures and grooves and it is suspected these are openings to its interior. A robotic explorer in the Uranian system will be able to uncover the origin of the carbon oxides on Ariel.

Without such a mission we are still somewhat in the dark given that Voyager 2 only imaged around 35% of the moon's surface.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.