Earlier this year, scientists stumbled upon a potential new treatment for hereditary-patterned baldness, the most common cause of hair loss in both men and women worldwide.

It all started with research on a sugar that naturally occurs in the body and helps form DNA: the 'deoxyribose' part of deoxyribonucleic acid.

While studying how these sugars heal the wounds of mice when applied topically, scientists at the University of Sheffield and COMSATS University in Pakistan noticed that the fur around the lesions was growing back faster than in untreated mice.

Intrigued, the team decided to investigate further.

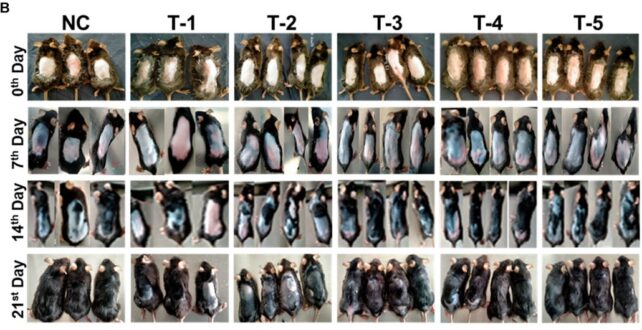

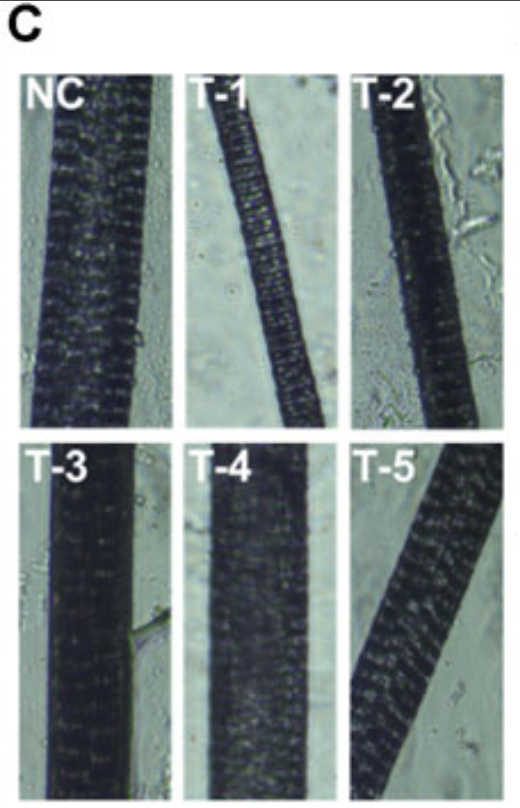

In a study published in June, they took male mice with testosterone-driven hair loss and removed the fur from their backs. Each day, researchers smeared a small dose of deoxyribose sugar gel on the exposed skin, and within weeks, the fur in this region showed 'robust' regrowth, sprouting long, thick individual hairs.

The deoxyribose gel was so effective, the team found it worked just as well as minoxidil, a topical treatment for hair loss commonly known by the brand name Rogaine.

"Our research suggests that the answer to treating hair loss might be as simple as using a naturally occurring deoxyribose sugar to boost the blood supply to the hair follicles to encourage hair growth," said tissue engineer Sheila MacNeil from the University of Sheffield.

Hereditary-patterned baldness, or androgenic alopecia, is a natural condition caused by genetics, hormone levels, and aging, and it presents differently in males and females.

The disorder impacts up to 40 percent of the population, and yet the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has only approved two drugs to treat the condition thus far.

While over-the-counter minoxidil can work to slow hair loss and promote some regrowth, it doesn't work for all those experiencing hair loss.

If minoxidil isn't effective, then male patients can turn to finasteride (brand name Propecia) – a prescribed oral drug that inhibits the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone. It's not yet approved for female patients.

Finasteride can slow hair loss in about 80 to 90 percent of male patients, but it needs to be taken continuously once it is started. The drug can be associated with unwanted, sometimes severe side effects, such as erectile dysfunction, testicular or breast pain, reduced libido, and depression.

"The treatment of androgenetic alopecia remains challenging," MacNeil and her colleagues, led by biomaterial researcher Muhammad Anjum from COMSATS, write in their published paper.

Together, the team designed a biodegradable, non-toxic gel made from deoxyribose, and applied the treatment to mouse models of male-pattern baldness.

Minoxidil was also tested on balding mouse models, and some of the animals received a dose of both sugar gel and minoxidil for good measure.

Compared to mice that received a gel without any medicine, those that received a gel with deoxyribose sugar began to sprout new hair follicles.

Both minoxidil and the sugar gel promoted 80 to 90 percent hair regrowth in mice with male pattern baldness. Combining the treatments, however, did not make much more of a difference.

Photographs were taken at various stages throughout the 20-day trial, and the effect is clear.

Researchers aren't sure why the deoxyribose gel stimulates longer and thicker hair growth in mice, but around the treated site, the team did notice an increase in blood vessels and skin cells.

"The better the blood supply to the hair bulb, the larger its diameter and the more hair growth," the researchers write.

If the deoxyribose gel also proves effective in humans, it could be used to treat alopecia or even stimulate hair, lash, and eyebrow regrowth following chemotherapy.

"This is a badly under-researched area, and hence new approaches are needed," write the authors.

The current experiments were only conducted among male mice, but further research might find the use of these natural sugars could also work for female mice experiencing testosterone-driven alopecia, too.

"The research we have done is very much early stage," said MacNeil, "but the results are promising and warrant further investigation."

The study was published in Frontiers in Pharmacology.

An earlier version of this article was first published in July 2024.