In a study of fruit fly (Drosophila) larvae, an international team of researchers has discovered how swallowing food is linked to the release of the feel-good chemical serotonin in the brain – offering new insight into how and why animals eat.

If the same mechanisms are present in humans, then this could be a fascinating insight into our own drive to consume food and drink.

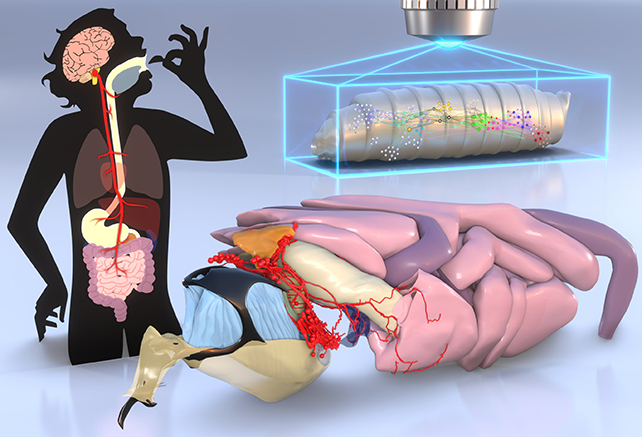

Scientists mapped the gut's enteric nervous system in the fruit fly in detail, and their findings shed new light on the vital act of swallowing: a behavior the researchers describe as "arguably the single most salient decision that an animal has to make".

"We wanted to gain a detailed understanding of how the digestive system communicates with the brain when consuming food," says neuroscientist Michael Pankratz, from the University of Bonn in Germany.

"In order to do this, we had to understand which neurons are involved in this flow of information and how they are triggered."

The researchers really went above and beyond in the course of their study: they carefully cut one of the larvae into thousands of tiny slices before photographing them under high-powered microscopes, mapping the paths of neurons and the connections between them.

A three-dimensional model was constructed from these photographs via computer software, leading to the discovery of a biological mechanism known as a stretch receptor, as in the esophagus, which connects the mouth to the stomach.

The receptor is connected to six specific neurons in the larva's brain, which get information about the swallowing action, and – crucially – what is being eaten. If good food is going down the pipe, the brain pumps out a reward.

"[The neurons] can detect whether it is food or not and also evaluate its quality," says neuroscientist Andreas Schoofs, from the University of Bonn.

"They only produce serotonin if good quality food is detected, which in turn ensures that the larva continues to eat."

Fruit flies have under 200,000 neurons in total, compared to the 100 billion or so in the human brain. However, the complexity in those thousands of nerve cells means they can act as a scaled-down version of the human body, which is easier to catalog – and here, revealing a basic driver behind a process every animal needs to survive.

The next stage is to see whether or not the same map of neurons and release of serotonin is present in other animals, including humans. We have more biological similarities with fruit flies than you might think, but a lot of scaling up will be required in this approach to know if this feel-good factor when eating is one of them.

"We don't know enough at this stage about how the control circuit in humans actually works," says Pankratz. "There is still years of research required in this area."

The research is published in Current Biology.