Editor's note (27 July 2020): This paper has been retracted by Nature due to suggestions the discovery may have been misclassified. There is now evidence the skull belongs to a lizard, which is a separate group of reptile to the dinosaurs.

Original (11 March 2020): A hundred million years ago, in the middle of the Mesozoic era, Earth was home to all sorts of dinosaurs - those both great, like the long-necked sauropod, and small, like the hummingbird.

As out-of-place as that sounds, palaeontologists now think the tiniest dinosaur in the Mesozoic was even more miniature than the smallest bird alive today, the bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae).

Found inside a chunk of 99-million-year-old amber from northern Myanmar, the skull of the newly identified dinosaur is only 7.1 millimetres long.

Artist's impression of Oculudentavis preying on an insect. (Han Zhixin)

Artist's impression of Oculudentavis preying on an insect. (Han Zhixin)

"When I first saw this specimen I was completely blown away," says Jingmai O'Connor in a YouTube video about the research.

"To a palaeontologist it's weird," she added. "We've never seen anything like it."

The team named their find Oculudentavis khaungraae, which means "eye tooth bird", and its appearance is every bit as mishmashed as its name.

The jaws on this little dino are lined with small pointy teeth; judging by the spoon-like sockets, the animal's two bulging eyes would have stood out in stark contrast to its tiny frame.

Artist's impression of Oculudentavis alive 99 million years ago. (Han Zhixin)

Artist's impression of Oculudentavis alive 99 million years ago. (Han Zhixin)

Frankly, it looks downright weird - not quite like a bird, nor quite like a dinosaur. But there are some clues that can tell us a little bit about its lifestyle.

The teeth, for instance, are a dead giveaway that the little dinosaur ate prey. And the openings in its eye sockets are quite narrow, which means light was probably restricted, implying activity in the daytime.

Plus, even though this dinosaur is so small, its bones are surprisingly robust and strong.

"To us the fact the skull is very fused, the fact it has lots of teeth, the fact it has these really big eye sockets, all suggests that despite its teeny, tiny size, it was a predator and it was probably feeding on small insects," says O'Connor.

A CT scan of the skull. (Li Gang)

A CT scan of the skull. (Li Gang)

All this points to Oculudentavis fitting in its own category, rather than being related to modern hummingbirds - because the flying jewels of today feed on nectar, and don't sport teeny tiny chompers. Thus, the researchers think creatures like the hummingbird took a different path to miniaturisation.

Weighing in at an estimated two grams, the team notes that Oculudentavis is about one-sixth the size of the smallest known early fossil bird - many of which did sport teeth, just like this little guy.

"This indicates that, only shortly after their origins late in the Jurassic period (which lasted from about 201 million to 145 million years ago), birds had already attained their minimum body sizes," Roger Benson, a paleobiologist from the University of Oxford who was not involved in the research, explains in an accompanying Nature News & Views piece.

"By contrast, the smallest dinosaurs weighed hundreds of times more."

It looks as though Oculudentavis might be one of those animals that stand on the stepping stone between dinosaurs and birds, but where exactly it fits into the larger picture is still not clear.

This feathered creature could belong more to the bird lineage or, as Benson explains, it could belong more to the dinosaurs, "lying almost midway on the evolutionary tree between the Cretaceous birds and Archaeopteryx, the iconic winged dinosaur from the Jurassic."

There are even some bizarre features, like the shape and size of the animal's teeth and eye sockets, that are not seen in either dinosaurs or birds. In fact, these more resemble… lizards.

"Nearly all of these unusual morphologies can be interpreted as the effects of miniaturisation," the authors write.

Take the bulging eyes on either side of the Oculudentavis head, for example. The location and size of these sockets probably represents an "alternative strategy for increasing eye size without further increasing the size of the orbit".

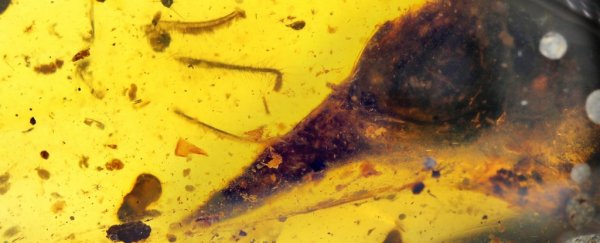

Burmese amber with Oculudentavis skull nearly perfectly preserved inside. (Lida Xing)

Burmese amber with Oculudentavis skull nearly perfectly preserved inside. (Lida Xing)

Unfortunately, that means this tiny dinosaur lacked binocular vision, which is a unique characteristic for a predator. Owls and other living birds of prey, for instance, have eyes pointed forward, but perhaps there's nothing out there quite like Oculudentavis today.

Getting trapped in amber is possibly one of the only ways for tiny organisms to be preserved as fossils. Soft tissue and fragile skeletons of this size are not typically preserved in other sediments, so in a study of miniaturisation, amber is a great place to start.

"Even in other places where you have exceptional preservation, small things might have existed but we don't have any evidence of it," says O'Connor in the video.

"So, if it wasn't for amber, we wouldn't know about this minute fauna at all. And it's just incredible to uncover this new ecological niche we never even knew existed."

The study was published in Nature.

Editor's note (27 July 2020): This paper has been retracted by Nature due to suggestions the discovery may have been misclassified. There is now evidence the skull belongs to a lizard, which is a separate group of reptile to the dinosaurs.