It all looked so promising. Ten years ago, a survey of mother humpbacks and their calves showed their numbers were on the up off the coast of Maui, Hawaii. Something has changed, with encounters plummeting by three quarters since 2013.

Of course, there could be a number of reasons behind the apparent decline in whale births. But the timing matches the appearance of a vast patch of warm water in the Pacific nicknamed 'the blob', and it's too much of a coincidence to ignore.

From 2008 until early last year, researchers from the Keiki Kohola Project and California State University would sit in the Au'Au Channel through the winter months wait to bump into passing humpbacks heading north to feed.

Of particular interest were mothers with newly born calves heading up from the warm southern waters, whose numbers would provide a fair indication of the health of whale populations in coming years.

For the first few years those statistics looked pretty good. The 2013 season saw on average a mother with her calf close to every three kilometres (1.9 miles), which is roughly triple 2008's numbers.

Warming waters around the Arctic has kept ice from returning quickly in the winter months, extending the feeding season for krill connoisseurs like the humpback.

Those few halcyon years didn't last though. Bumping into a newborn has since become increasingly rare. Combined figures for 2017 and 2018 saw on average a single pairing about every 12 kilometres.

Behavioural ecologist Alison Craig from Edinburgh Napier University suggests it's possible, but unlikely, that the whales are out there, simply avoiding the run through Hawaii. Craig wasn't involved with the study itself, but did offer National Geographic her perspective.

"There are a number of areas nearby that aren't as well studied where females might potentially also go to breed, and we should certainly keep an eye on those," Craig told National Geographic's Tim Vernimmen.

"But in my experience, humpbacks are quite conservative, breeding and feeding in the same places for decades."

She also pointed out that the study's worrying figures reflect a similar trend in whale numbers off the Alaskan coast, making them hard to ignore.

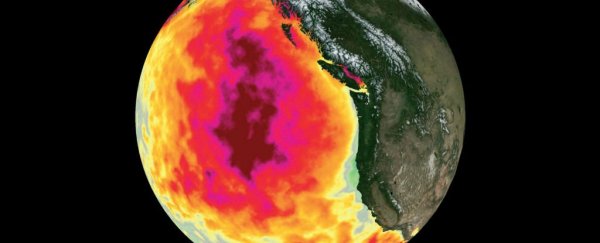

If the numbers are an accurate depiction of a decline in the humpback calf population, something has put a halt on 2013's baby boom. A strong contender for a cause is the presence of a wide swathe of warm water dubbed 'the blob', defined by a stark contrast in temperature of a few degrees Celsius.

This hundred-metre-deep patch of warm water was first noticed in 2013 in the Gulf of Alaska, but has since drifted down the North American coast and stretched out around 1,600 kilometres (about 1,000 miles) towards the west.

These days it's more like a small family of blobs, having split into several zones that occupy the Bering Sea, the California coast, and the coast from Oregon to Canada.

But in the years immediately after its discovery the anomaly was wreaking havoc with the weather across the US.

Throw in the 2014 to 2016 El Niño event and a warm change in 2014 for what's known as the Pacific decadal oscillation, and those few years start to look decidedly toasty in that corner of the globe.

All of that heat would have been bad news for whale's favourite food. Krill are partial to cooler conditions, so when the temperature starts to climb there's less for the whales to feast upon.

This doesn't necessarily mean the whales are starving. But for female humpbacks to ovulate, they need a good layer of fat cells to pump out sufficient amounts of a hormone called leptin.

Less krill means less fat. And since less fat means less chance of having eggs to fertilise, it could explain why there aren't as many mothers and calves seen coming up from the breeding grounds in the south.

Whales are far from the only animals to potentially suffer the effects of the blob. Several years ago, an unusual number of malnourished and dead sea lion pups were linked to the Pacific's warm patch. A rise in sea bird deaths have also been pinned on the blob's heat.

The good news is the researchers have noticed the whale numbers are again on the rise with a weakening in the blob.

"I just came back from Hawaii, and the numbers of moms and calves are back at the level of 2014 now," Keiki Kohola Project leader Rachel Cartwright told Vernimmen.

Still, the research doesn't bode well for marine life facing a future of warming oceans.

Blobs are looking like the new norm, and in spite of the promise of Arctic feasts, whales might face many more challenges like this one when it comes to growing their family.

This research was published in Royal Society Open Science.