The Anak Krakatoa volcano in Indonesia - the so-called "Child of Krakatoa" - was formed by one of the most deadly volcanic disasters in modern history. Last year, unbeknownst to the world, it was close to unleashing something similar.

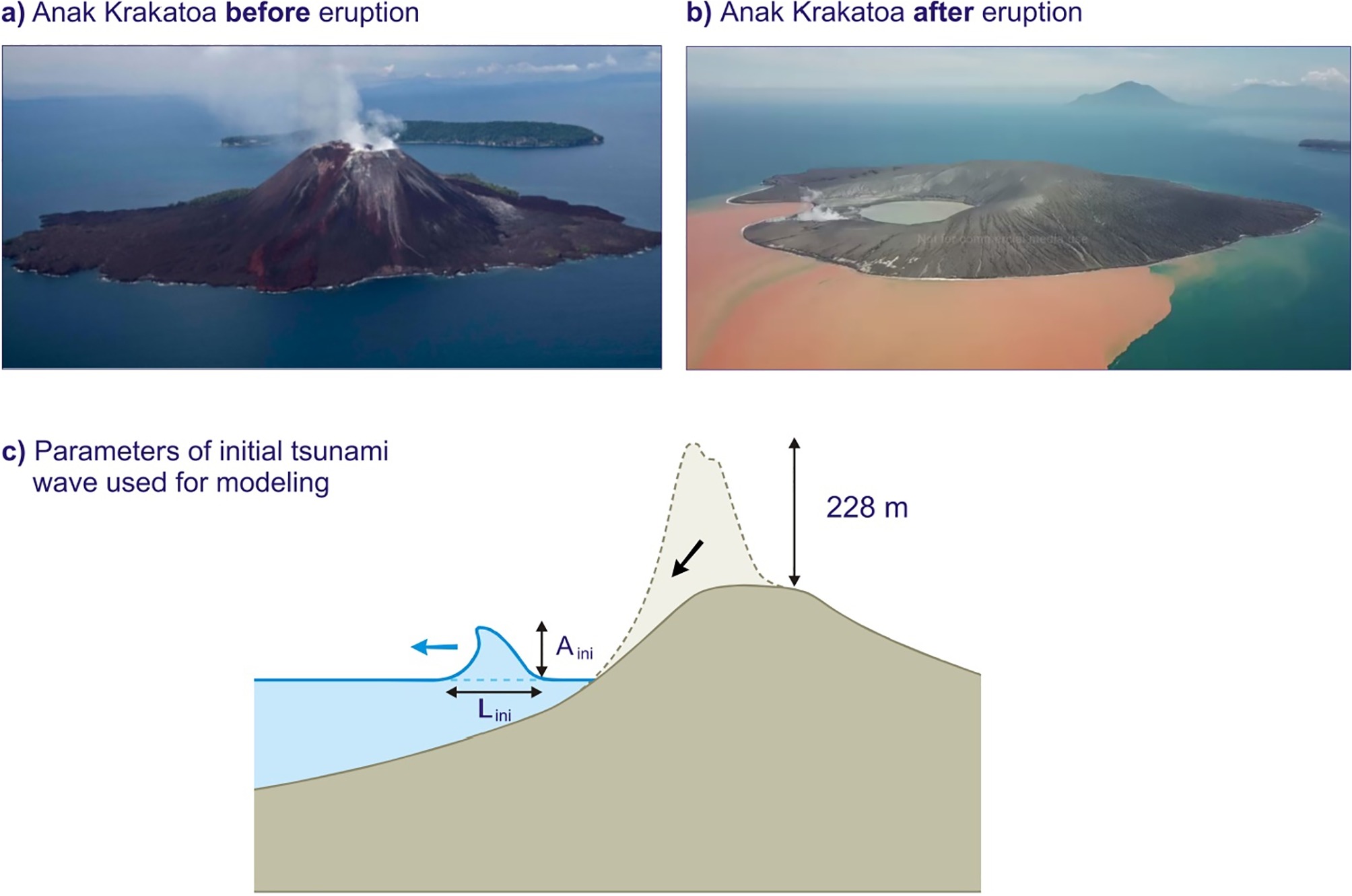

In 2018, as Anak Krakatoa violently erupted, its middle suddenly collapsed, triggering a tsunami that claimed more than 400 lives on the islands of Sumatra and Java.

When the waves reached civilisation less than an hour after the trigger, this wall of water was more than 10 metres (32 feet) high. And yet, researchers from Brunel University London and the University of Tokyo say, this was a mere fraction of its former glory.

At its peak, they estimate, the tsunami was anywhere between 100 and 150 metres tall (330 to 490 ft), which is larger than the Statue of Liberty and at least as high as London's Big Ben.

As these huge waves sped across the ocean, like ripples in a pond, they gradually shrank from gravity and friction until, at some 80 metres high, they finally hit land.

"Fortunately, nobody was living on that island," says civil engineer Mohammad Heidarzadeh from Brunel University.

"However, if there was a coastal community close to the volcano - say, within 5 kilometres - the tsunami height would have been between 50 and 70 metres when it hit the coast."

At heights like this, the results would have been catastrophic. In 1883, the notorious Krakatoa eruption, which occurred around the same place, triggered a massive tsunami that claimed the lives of some 36,000 people. At its peak, that tsunami was only 42 metres high, and the islands it struck were far less populated than today.

In short, the results suggest that if the Anak Krakatoa tsunami had been travelling in another direction, it might have been one of the worst natural disasters of our time.

Drawing upon sea-level data from five locations around Anak Krakatoa, researchers created a computer simulation of the tsunami and its movements under 12 different scenarios.

"The measurements were done by wave gauges operated by the government of Indonesia," explains Heidarzadeh.

"We used that real data to make sure that our simulations are consistent with reality - it's extremely important to validate computer simulations with real-world data."

(Mohammad Heidarzadeh)

(Mohammad Heidarzadeh)

Unlike previous models, which suggest the wave had several peaks, the new results indicate the initial wave was shaped almost like a pure wave hump, or an elevation wave.

Standing more than 100 metres high and up to 2.5 kilometres (1.5 miles) long, this powerful body of water would have produced similar energy to an earthquake sitting at 6.0 or 6.1 on the Richter scale.

That's exceptionally strong compared to most other tsunamis, and it's the first evidence to show such a huge wave can be generated by a volcanic eruption.

Tsunamis of this kind don't happen very often, which makes them hard to study. What happened in 2018 is therefore fascinating, and because it was recorded on several tide gauges, it can tell us a lot about how these events begin and propagate.

Most tsunamis are actually very weak and are usually only a few centimetres high. Even larger cases are generally around 10 to 20 metres high (30 to 70 feet), but tsunamis generated from landslides have the potential to be much larger.

In Italy in 2002, for instance, the Stromboli volcanic eruption collapsed and triggered an 8-metre-high wave. Just a few years ago in Greenland, a massive landslide caused a 100-metre-high tsunami that killed four people when it crashed into a remote fishing village.

So far, these natural disasters have managed to avoid the more populated areas, but that's just a matter of luck. Indonesia is home to about 130 volcanoes, many of which sit near the sea and are capable of producing tsunamis.

The devastation of Krakatoa is a reminder of what can happen in the worst case scenarios, and last year, it seems as though the world narrowly avoided exactly that.

The study was published in Ocean Engineering.