If you're the type who fusses over recycling and using cold water to save the planet, boy do we have some news for you.

Research shows that the best ways to cut down on your carbon footprint are actually not the ones typically recommended by governments and textbooks. And there's one life choice in particular that makes the most radical difference.

As the world is struggling to limit future global warming to below 2°C, now is the time when everyone must chip in to cut back our greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible. While most of the onus lies on governments and the fossil fuel industry, those reforms will inevitably take decades.

But even on a personal level, we all make a daily environmental impact. We can shift our choices relatively quickly, and they can spread through society as widely accepted behaviour.

With this in mind, two researchers from Lund University in Sweden and the University of British Columbia in Canada set out to analyse "a comprehensive suite of lifestyle choices to identify those with the greatest potential to reduce individual greenhouse gas emissions."

They looked at 39 peer-reviewed studies, government reports and online tools to pick lifestyle choices promoted to reduce our carbon footprints. Then they ran estimates on how impactful these actions really are if you live in the developed world.

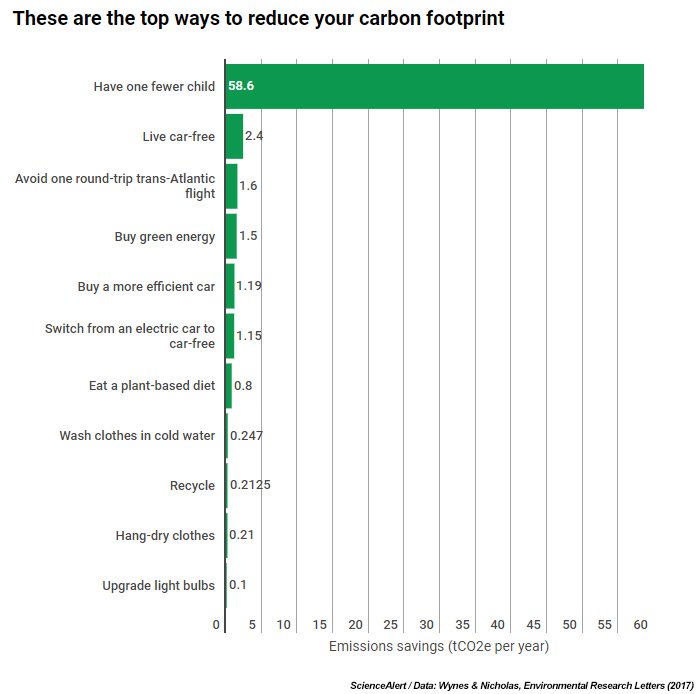

According to their analysis, here are the top four things that will make the highest impact on your personal emissions: ditch your car, avoid airplane travel, switch to a plant-based diet and, most radically, have fewer offspring.

Measured in tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions (tCO2e), these lifestyle changes have a much greater potential to cut back on our personal carbon footprints than 'little things' like recycling and swapping out your incandescent light bulbs for long-life ones.

"We provide mean values for our recommended actions, but we do not suggest that these are firm figures universally representative of each action, but instead best estimates," the researchers write.

While there's some uncertainty over the true environmental value of everyone going vegetarian, it appears that in relative terms vegetarians really are helping the planet a bit more.

The team's data show that if you stop eating meat for a year, your individual carbon footprint can drop by 820 kilograms of CO2, which is on average four times more effective than recycling.

The study also found that textbooks intended for adolescents and government materials actually don't endorse these higher-impact actions, instead promoting choices more along the lines of ditching plastic bags.

Based on their analysis, the researchers argue it's time to change this and recommend higher-impact actions even if we don't think everyone can switch over to doing those.

"Serious behavioural change is possible; there is evidence that younger generations are willing to depart from current lifestyles in environmentally relevant ways," the team writes in their study.

They do admit that some of the high-impact actions are "politically unpopular" choices. But what matters here is whether we're actually cutting back emissions in a meaningful way, or just making ourselves feel better by hanging socks on the washing line.

Our small everyday contributions to sustainability are absolutely valuable as they do add up, but research shows they don't necessarily lead to a 'positive spillover' of environmentally friendly choices at a more impactful level.

In other words, plenty of people who separate their recycling also drive massive petrol-guzzling cars. But if we make bigger sacrifices for the sake of the planet, there's more scope to change societal norms as a whole, the team argues.

Of course, it's not feasible for all of us to convert to vegan hermits who only travel on foot. But this new data are certainly food for thought, especially as we face up to the reality of future generations living their lives on an inevitably hotter planet.

The research was published in Environmental Research Letters.

A version of this article was first published in July 2017.