Dementia is a thief that picks many pockets. In some guises, it takes our memories. Other forms rob us of inhibition. Sometimes it even takes away happiness itself.

A new study has shown for the first time how some forms of early-onset dementia are associated with a profound loss of pleasure linked to a wasting of 'hedonic hotspots' – brain regions associated with reward seeking.

An absence of pleasure is known as anhedonia, and it's a common symptom in mental health conditions such as depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Where most of us are rewarded with a sense of satisfaction, excitement, and bliss when we achieve a goal or associate with loved ones, those experiencing anhedonia can't.

Interestingly, early dementia is often confused with depression, and a decline in motivation can be used as a criterion for diagnosis. So researchers from the University of Sydney and University of New South Wales in Australia decided to formally investigate this link between anhedonia and types of dementia for what they believe is the first time.

"Much of human experience is motivated by the drive to experience pleasure, but we often take this capacity for granted," says neuroscientist Muireann Irish from the University of Sydney.

"But consider what it might be like to lose the capacity to enjoy the simple pleasures of life – this has stark implications for the wellbeing of people affected by these neurodegenerative disorders."

In the study, the researchers assessed 121 patients diagnosed with various forms of dementia to determine who was more likely to suffer from the clinical symptom of anhedonia.

Out of the group, 87 patients had 1 of 3 different types of frontotemporal dementia (FTD). FTD is an earlier-onset dementia, with symptoms usually starting between the ages of 40-65.

One FTD variant affects the frontal lobe, messing with an individual's personality and emotional responses. A second variant strikes the temporal lobe, reducing the person's reading and comprehension. The rarest of the three presents as a form of aphasia, reducing their capacity to communicate through speech.

The team used several assessment tools to measure the prevalence of anhedonia in each subset of FTD as both a solitary symptom and as a feature of depression and a general lack of motivation.

The results were compared with those gathered through similar evaluations conducted on 34 volunteers with Alzheimer's and 51 otherwise healthy older participants.

They found those with frontal and temporal forms of FTD – clinically referred to as behavioral-variant FTD and semantic dementia – were far less likely to experience joy than they did before their diagnosis, compared with those with the rarer aphasia variant or Alzheimer's disease.

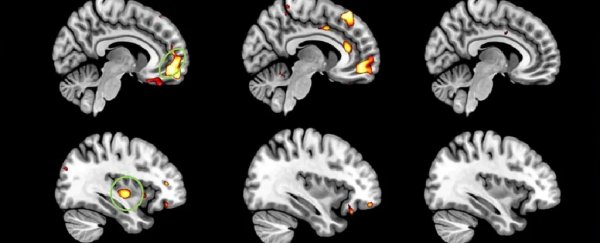

This finding was reflected in a mapping of the patients' tissue densities across their entire brains, which repeatedly revealed a loss of cells in areas such as the orbitofrontal and prefrontal cortices, insular cortex, as well as the putamen. These regions are linked to the brain's pleasure systems.

Importantly, the atrophy associated with anhedonia was distinct from the changes linked to apathy or depression.

Regions circled in green are linked to pleasure and reward seeking. (University of Sydney)

Regions circled in green are linked to pleasure and reward seeking. (University of Sydney)

The discovery may seem bleak, but it could help doctors better diagnose, and eventually treat the disease.

"Our findings also reflect the workings of a complex network of regions in the brain, signaling potential treatments," says Irish.

"Future studies will be essential to address the impact of anhedonia on everyday activities, and to inform the development of targeted interventions to improve quality of life in patients and their families," says Irish.

This research was published in Brain.