A baby bumblebee in the hive is protected from the outside world like a fetus in the womb. Yet when contaminated foods are brought back to the colony, that isolation is put at risk.

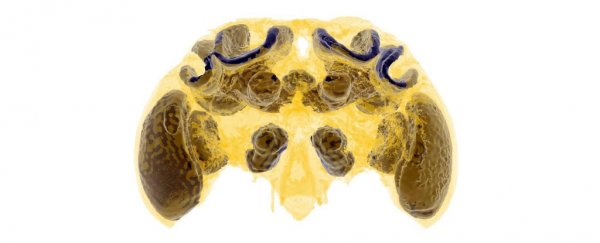

New research suggests when young larvae are exposed to pesticides it may cause lasting and irreversible damage to their brains as adults. Using micro-CT scanning, researchers have found these harmful chemicals can stunt a bee's development, reducing its ability to forage for food once it's left the hive.

"Bee colonies act as superorganisms, so when any toxins enter the colony, these have the potential to cause problems with the development of the baby bees within it," says ecologist Richard Gill from Imperial College London.

"Worryingly in this case, when young bees are fed on pesticide-contaminated food, this caused parts of the brain to grow less, leading to older adult bees possessing smaller and functionally impaired brains; an effect that appeared to be permanent and irreversible."

To date, the authors say this is the first study to investigate how pesticides impact early development in bumblebees. And the results aren't exactly promising.

In the study, a colony of bees was provided with a nectar that had been spiked with a widely-used class of pesticides, known as neonicotinoids.

When the young finally flew out of the hive as working adults, their learning abilities were tested twice: once, three days after they had emerged, and another test at 12 days of adult life.

To test their learning skills, the bees were given a smell along with a food reward. They were then scored on how well they could associate the two factors over the course of ten trials.

Afterwards, the results were compared to a second colony, which had been fed no pesticides, and a third colony, which had been fed pesticides only as adults.

In the end, those larvae that were exposed to pesticides grew up to suffer significant learning impairments, which looked similar at both three and 12 days of adult life.

Yet even when bees were exposed to pesticides only as adults, the impact was drastic. After just three days of eating contaminated nectar, adult bees showed the same degree of learning impairment as the larvae that had been exposed for weeks on end.

Scanning the brains of nearly 100 bees from all three colonies, the authors say exposure to pesticides at both stages - whether larvae or adult - was linked to a smaller part of the insect brain, known as the 'mushroom body'.

This tiny structure, just a few millimetres wide, is associated with insect learning, and in just three days of pesticide exposure as an adult bee, this region was unable to grow as normal.

"Together these findings highlight that the first 72 [hours] of adulthood must be important in behavioural development," the authors conclude, "but also represents a susceptible developmental window to insecticide exposure showing the importance of considering different life-stages when assessing pesticide risk."

When exposed as a larvae, for instance, the effects appear to last for weeks. There was a clear increase in mushroom body size and learning scores seen in the controls, but this relationship was not present in the bees exposed to pesticides, suggesting the function of this brain region had been disrupted.

While most previous studies have focused on pesticide exposure in adult bees, this new research suggests baby bees can also feel the effects of the contaminated food.

"There has been growing evidence that pesticides can build up inside bee colonies," says Dylan Smith, who studies environmental impacts on insects at Imperial College London.

"Our study reveals the risks to individuals being reared in such an environment, and that a colony's future workforce can be affected weeks after they are first exposed."

This lag-effect might help explain why in the past, bee colony growth has fallen two or three weeks after exposure to these pesticides. With very little recovery seen in adults over the course of nine days, the authors worry the consequences could be permanent.

Today, bumblebees are facing an uncertain future. In the last century alone, their numbers have plummeted by more than 30 percent in both Europe and America.

Of course, not all of this is from pesticides. Bees also are contending with rising temperatures and habitat loss. But figuring out how and why these colonies are disappearing may be our only chance to save vital pollinators for the future.

"These findings reveal how colonies can be impacted by pesticides weeks after exposure, as their young grow into adults that may not be able to forage for food properly," says Gill.

"Our work highlights the need for guidelines on pesticide usage to consider this route of exposure."

The study was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.