We humans may no longer have tails, but perhaps we have more in common with our smaller primate relatives than we thought.

An analysis of accidentally broken stones used by macaques to crack nuts shows that monkeys have inadvertently been fracturing chunks of rock startlingly similar to the intentionally-created tools found at the world's earliest known archaeological sites in Africa.

This discovery could help scientists contextualize how ancient humans developed their first forms of technology.

The finding raises the possibility that hand-crafted tools were initially the result of incidental use. As stones where smashed against larger anvils – a behavior still seen among crab-eating or long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in Thailand – sharp flakes of stone that broke free may have provided the community with another useful instrument by happenstance.

"The ability to intentionally make sharp stone flakes is seen as a crucial point in the evolution of hominins, and understanding how and when this occurred is a huge question that is typically investigated through the study of past artifacts and fossils," says paleolithic archaeologist Tomos Proffitt of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

"Our study shows that stone tool production is not unique to humans and our ancestors."

The development of stone tools is considered a pivotal moment in human history, having been traced back millions of years. Early stone tools, found in significant numbers in sites with the remains of ancient hominids that include the ancestors of modern humans, were fairly simple. They were stone cores that had been shaped to create a sharp edge used, archaeologists believe, for cutting, chopping, scraping, and butchering.

Yet from these simple tools, more and more complex technology ensued.

Tool use is not unique to humanity, however, and there are a number of primates that are known to use stones to perform percussive tasks – cracking open nuts or shellfish, grinding seeds, and digging up roots. Crab-eating macaques have been using rocky materials for possibly thousands of years to crack open nuts and oysters, and their range is littered with the broken shards of stones that have broken from use.

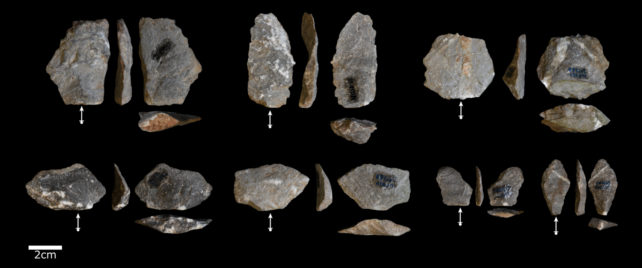

Proffitt and his colleagues collected a number of these broken pieces and conducted a thorough analysis, comparing them to stone tools used by ancient humans. And they found that, in the absence of behavioral evidence, archaeologists may have interpreted the macaque fragments as evidence of intentional tool manufacture.

"The fact that these macaques use stone tools to process nuts is not surprising, as they also use tools to gain access to various shellfish as well," Proffitt explains. "What is interesting is that, in doing so, they accidently produce a substantial archaeological record of their own that is partly indistinguishable from some hominin artifacts."

When cracking nuts or oysters, macaques regularly and unintentionally produce stone flakes of a conchoidal shape with a sharp edge similar to those seen in the hominid archaeological record. The macaques are not known to use these flakes; once a stone tool is broken, the shards are useless to the macaques, and they go on to find other tools.

The team carefully studied these broken flakes, and found that they often had attributes used to diagnose intentionally made stone tools from archaeological sites. Perhaps that's not surprising; the macaques crack open nuts by placing them on a stone anvil, then hitting them with another stone. Early stone tools were made by hitting stones with other stones. The action and outcome are similar; it's the intent that differs.

The dataset, the researchers say, represents the biggest dataset of percussive flakes and flaked stones produced by non-human primates to date, and could help distinguish between human and non-human primate flake production in the future.

In addition, it could offer a window into our own past.

"Cracking nuts using stone hammers and anvils, similar to what some primates do today, has been suggested by some as a possible precursor to intentional stone tool production," says archaeologist Lydia Luncz of the Technological Primates Research Group at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

"This study, along with previous ones published by our group, opens the door to being able to identify such an archaeological signature in the future."

The research has been published in Science Advances.